There are three inter-related areas where action is urgently required to avert further rapid environmental degradation:

-

Mandatory environmental target setting and the integration of environmental targets into medium-term government strategy and fiscal policy setting.

-

National State of Environment reporting.

-

˜Green budgeting’ – the use of the budgetary system to improve environmental outcomes.

The twin climate change and environmental degradation crises show emphatically that current approaches to environmental stewardship are failing miserably. While myopically protecting the over-consumption of natural capital and imposing increasing negative effects on current generations, especially the poor, we are leaving a legacy of mind-boggling cost and risk for the generations that will follow. UNEP’s 2018 Global Environment Outlook (GEO 6) ˜provides the evidence thatwithout a fundamental redirection, most environmental domains will continue to degrade, threatening the economic and social progress achieved to date and the fate of the multiple species that share planet Earth.’

Many factors contribute to global environmental degradation, but one that has received surprisingly little attention is the lack of government transparency and accountability for environmental stewardship compared to other policy domains, such as fiscal and monetary policy, and the systematically weak integration of environmental stewardship into overall government strategy.

While international initiatives such as the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the Aichi Bio-diversity Targets, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are crucial to galvanise coordinated action, international treaties and agreements can in general only be implemented by sovereign states passing and implementing domestic laws.

However, compared to the way in which many governments now manage the public finances – based on commitments in domestic law to publish goals, targets and progress reports – the arrangements for environmental stewardship are primitive.

Many governments get away with longer-term unquantified ˜feel good’ goals for the environment “ such as ˜reversing loss of biodiversity’, ˜or cleaning up waterways’ – without the discipline that comes from being required to regularly report to the legislature on the intended path to the goals, interim milestones, recent progress, and what they are doing now to promote their achievement.

In other cases, such as climate change, governments sign up to ambitious quantitative targets, but ˜the vast majority of countries have [national] targets that are woefully inadequate and, collectively, have no chance of meeting the 1.5°C temperature goal of the Paris Agreement’ (Climate Action Tracker, 2019).

˜A goal without a plan is just a wish’ – Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

Or a political deceit.

Imagine any government today telling the electorate that it will reduce public debt by 20 per cent of GDP in twenty years’ time but providing no report on last year’s budget outturn, no current data on public debt, presenting no forecasts and no budget for next year, and talking only in general terms about how it will achieve the goal!

Of course, environmental outcomes result from the complex interplay of natural processes, human activities, and central, regional and local government actions. They cannot be managed in the same way that a government can manage its finances.

Nevertheless, there is an urgent need to apply to national environmental stewardship a broadly comparable underlying framework of mandatory transparency of goals and targets and ex post accountability. Prompted by international climate change treaties, this approach is being applied by a few governments to carbon emissions following the UK’s pioneering Climate Change Act 2008, with its statutory requirements for 5 yearly carbon budgets, an independent watchdog, and comprehensive reporting. This general approach is required across all environmental domains.

Environmental goals and targets must then be integrated into overall government strategy and the medium-term strategy process that drives the annual budget. While government regulation is critically important to environmental outcomes, there is no regulatory policy cycle or equivalent of the annual budget as a focus of coordinated policy action and prioritisation. And in countries with multi-year national planning frameworks, these must be implemented in large part through annual budgets.

The budget is therefore typically a government’s single most important expression of its actual strategies and priorities, and potentially its most powerful cross-sector policy integration tool. If environmental goals and targets are to mean anything, they need to be more effectively mainstreamed i.e. incorporated in the (medium-term) strategy process that drives or shapes the annual budget “ as recognized by the Helsinki Principles adopted in 2019 by the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action.

Yet fiscal strategy setting around the world remains dominated by assessment of macroeconomic and fiscal statistics and associated risks. Information on environmental outcomes and risks, and interactions between the environment and the economy, (such as the UN System of Environmental “Economic Accounting), needs to be integrated into decisions on the medium-term fiscal strategy. In New Zealand an amendment to the Public Finance Act under consideration would require every Government to draw a connection between its wellbeing objectives and its fiscal policy and to report on environmental and social indicators alongside macroeconomic and fiscal indicators.

The setting of targets for environmental outcomes should be based on national State of Environment Reports (SoERs). The regular publication of SoERs followed the call by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro for nations to issue reports on the environment that would complement traditional fiscal policy statements, budgets, and economic development plans. The 1995 UN Commission on Sustainable Development introduced the ˜Drivers, Pressures, State, Impact, Response’ (DPSIR) model of environmental reporting widely used today.

Most advanced countries, including all members of the European Environment Agency (EEA), many middle-income countries, and some developing countries publish national SoERs, typically 3-5 years. These reports contain a large number of physical outcome indicators across all environmental domains, including biodiversity loss, land degradation, air, land and water pollution, water and natural resource management, and climate change. The data is captured mainly by national and sub-national environmental monitoring systems.

However, SoERs invariably have gaps in the data and/or its analysis of varying severity reflecting resource and capacity constraints. There may be concerns about technical independence of the reports (e.g. with respect to NZ’s 2007 SoER). Many of them are backward-looking, reflecting the DPSIR framework, although some include assessments of outlooks and/or scenarios, and a few contain policy recommendations e.g. the Dutch SoER 2014. The reports often fail to highlight the areas of critical concern amongst a large number of environmental indicators. Nor are governments required to respond to each report or to indicate what they are doing and will do to avert further environmental degradation. SoERs may be largely ignored or quickly forgotten.

The importance of national capacity for data collection and monitoring is recognized in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 17 on strengthening the means of implementing the SDGs. Reflecting this, UNEP calls in GEO 6 for improved national environmental monitoring and reporting systems using a combination of enhanced national data collection and better use of existing data, remote (satellite) observation systems, and citizen environmental monitoring. UNEP has a current project assessing country needs in environmental statistics collection and reporting.

National environmental reporting should be introduced in countries that do not yet publish SoERs – especially in megadiverse countries – and focusing particularly on critical environmental indicators. And where environmental reporting is in place the framework should be progressively strengthened in a number of ways:

- Each report should be compiled by an entity with technical independence from government (as is the case, for example, in the Netherlands).

- Each report should include forward-looking data on outlooks and scenarios, including risks and tipping points with respect to critically important indicators (for example, the Australia SoER 2016 contains information on resilience, risks, and outlook scenarios).

- The environment ministry should provide timely and comprehensive policy advice to government in response to the data and analysis in the SoER.

- There should be a legislative requirement for the government to respond to each SoER stating its assessment, its top priority environmental outcomes, strategies, targets, milestones, and recent progress. For example, Sweden has since 1999 pioneered transparency of national environmental goals, targets, and progress reports based on a system of environmental quality objectives (EQOs) set by Parliament (although not in law). The prospects for achieving the EQOs are assessed each year and are incorporated in the government’s annual progress report to Parliament.

- Each SoE report should in the normal course of events be published within a certain time prior to each national election “ similar conceptually to the pre-election fiscal update required by the OECD Best Practices in Budget Transparency 2002, intended to strengthen public accountability.

Thirdly, all governments should progressively introduce ˜green budgeting’. Fiscal policies “ taxation and government spending – have major environmental impacts. Green budgeting will help to realise Principle 4 of the GIFT High-Level Principles of Fiscal Transparency, Participation and Accountability: ˜Governments should communicate the objectives they are pursuing and the outputs they are producing with the resources entrusted to them, and endeavour to assess and disclose the anticipated and actual social, economic and environmental outcomes‘.

Some of the environmental impacts of fiscal policy are positive: funding for management of the public conservation estate, and environmental protection expenditures. Public spending also has indirect positive impacts on environmental outcomes through the level of funding for environmental regulation, and public funding of environmental monitoring, reporting and research.

Other environmental impacts are negative, such as those from fossil fuel and agricultural subsidies or subsidised water and electricity consumption, and from large public infrastructure projects. The OECD has assessed that between 2010 and 2015 direct government expenditure on subsidies to fossil fuels amounted to US$373-617 billion annually across 76 economies which collectively contribute 94% of global carbon emissions. In contrast, the amount those governments spent on biodiversity was only around one tenth of that amount. There is also the risk of lock-in of environmentally damaging technologies through new public infrastructure investment e.g. in electricity generation.

In addition, the tax system is an important tool to ˜correct’ the prices of activities that generate unpriced social costs (externalities), such as the social costs of carbon emissions or of pollution. Yet formal carbon pricing schemes (carbon taxes and emissions trading systems) cover only about 15% of global emissions (World Bank State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2019), although existing road fuel taxes and royalties imposed for non-climate policy reasons imply taxes equivalent to US$33 and US$10 per tonne of CO2 respectively (IMF 2019).

What does green budgeting comprise? The OECD launched the Paris Collaborative on Green Budgeting in December 2017. The objective of green budgeting is to use the tools of budgetary governance to help drive improvements in the alignment of national expenditure and revenue processes with climate and other environmental goals. This requires establishing clear connections between public finance and environmental impacts.

The OECD has identified a potential set of specific components of green budgeting, to be progressively developed and introduced. These might all be included in a single annual ˜Green Budget Statement’, or some elements may be incorporated in existing budget documents depending on what is appropriate in individual country settings. As defined by the OECD the components include:

- A description of the anticipated environmental impacts of the new policies being introduced in the annual budget.

- An analysis of the environmental impacts of various areas of the revenue and expenditure baseline (on-going policies). This should cover direct spending, grants, loans, contingent instruments, revenue policies including tax expenditures, and other fiscal opportunity costs e.g. non-auctioning of rights to pollute.

- An assessment of the use of the tax system to ˜price’ environmental externalities (including carbon emissions).

- Cross-national benchmark indicators of progress.

The OECD also recommends periodic (less than annual) supplementary reports:

- A Green Budget Fiscal Sustainability Report incorporating prospective environmental impacts into long term fiscal sustainability analysis;

- A Green Balance Sheet, to report the value of natural assets and liabilities in the context of the government’s financial balance sheet.

In addition to these elements, consideration should be given to production and publication of:

- An annual Green Performance Budget Report linking the programs/outputs funded in ministry budgets through intermediate progress indicators to the high-level environmental outcome targets.

- The interactions between fiscal policies and environmental regulation e.g. adequacy of funding of environmental regulation, the revenue potential of cap and trade schemes and any foregone revenues from differential treatment of sectors, ˜feebate’ approaches to reducing environmental externalities, and the fiscal and distributional impacts of greenhouse gas liabilities.

- An assessment and, to the extent feasible, quantification of the economic impact of recent degradation of ecosystem services at the margin in a selected high priority sector, and the estimated cost of restoration of ecosystem services.

- As feasible, an assessment of environmental resilience, and short to medium term risks around critical environmental outcomes, and threats to long term sustainability.

- A periodic monitoring and evaluation (M&E) stocktake of the evidence on the efficiency and effectiveness of government interventions in achieving environmental objectives, and identification of research priorities. Sweden publishes a four-yearly environmental M&E stock-take.

All budget documents should incorporate all public funds, including all climate and other environment finance flows that may be ˜off-budget’ and all public receipts of international climate change mitigation or adaptation funds (International Budget Partnership 2018).

Technical work is underway to support better understanding of the impacts of fiscal policies on the environment, including the OECD’s Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment 2018, and a spreadsheet tool developed by the IMF incorporating domestic externalities from fuel use to help countries evaluate progress towards their Paris mitigation pledges.

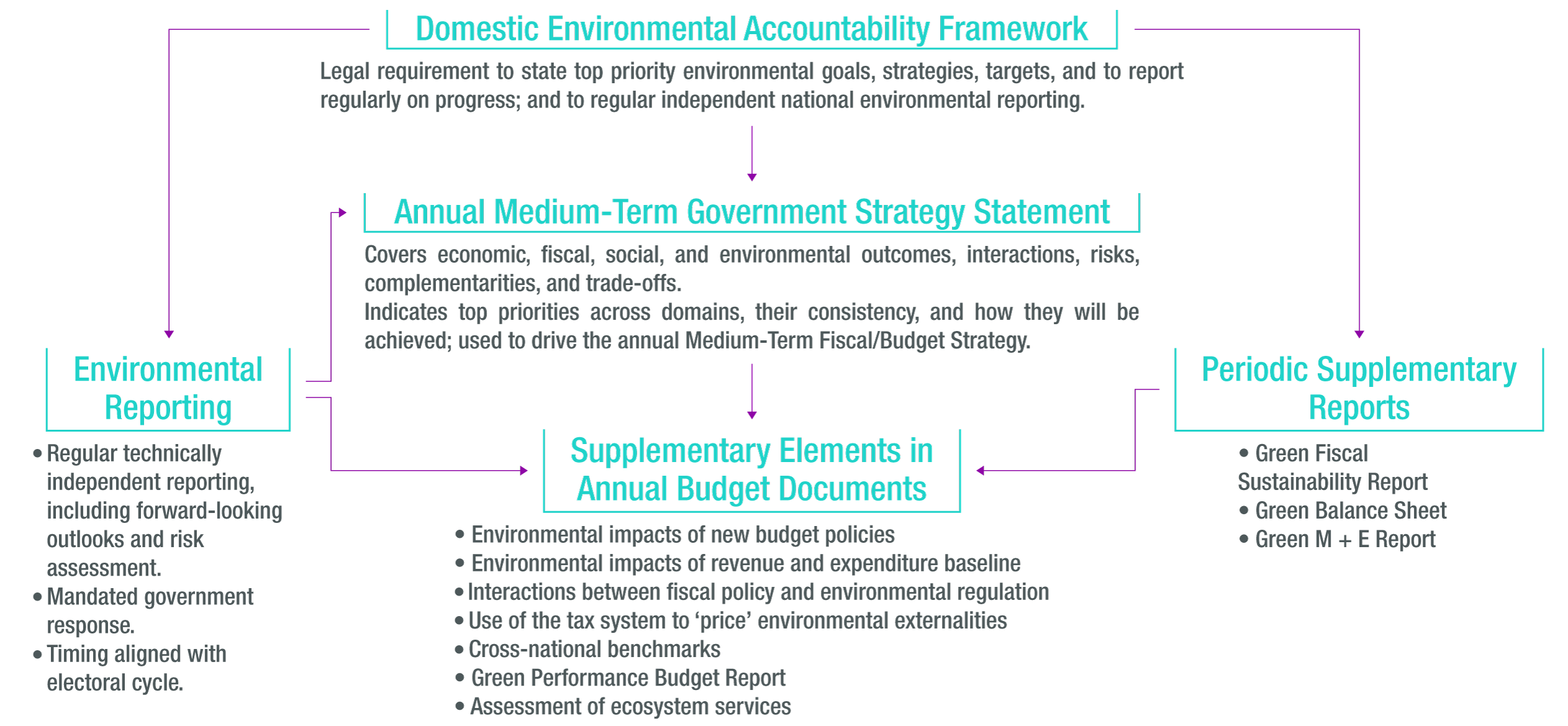

Pulling the three priority areas together, Figure 1 illustrates the combination of initiatives put forward in this article.

Figure 1: Comprehensive Framework for Environmental Accountability

Some governments have started on this path. As noted, the UK’s Climate Change Act 2008 represents this type of self-imposed mandatory target setting/verification/reporting approach applied to one (major) environmental outcome. The approach in Figure 1 would see this extended across all environmental domains. This would be similar to Sweden’s approach to setting environmental quality objectives. Other countries to take steps in this direction include the Netherlands where the SoER contains an evaluation of the degree to which short-term quantitative environmental targets set by the Cabinet are projected to be achieved through current policy; and England where there is regular reporting on progress against 24 indicators from the government’s Biodiversity 2020 Strategy.

Other governments have started to integrate climate change and wider environmental sustainability into the budget process. Norway ˜s 2016 Budget contained a detailed section on Sustainable Development and Green Growth, including a discussion of the use of taxes to improve resource efficiency, the country’s performance on climate change, the state of ecosystems, and management of renewable resources. France is introducing a comprehensive reporting structure for climate economic analysis in its annual budget documents and intends to add data on public and private expenditures aligned with environmental targets. Prompted by the requirements for issuing Green Bonds, Ireland is identifying the amount of government spending dedicated to addressing climate change and intends subsequently to introduce assessments of the environmental impacts of public spending. The 2019 Budget in New Zealand was presented as a ˜well-being budget’ in which a wider set of social and environmental indicators and objectives was integrated into budget decision-making

There is a huge opportunity to build on these developments. A renewed international effort is needed to expand and deepen national SoER reporting and to build the national capacity for environmental data collection. There is an important role for the UN system and multilateral and bilateral development agencies to finance national capacity development in environmental statistics collection as well as remote measurement systems. International organizations such as the OECD, World Bank, and the IMF, international multi-stakeholder networks such as GIFT and the Open Government Partnership, and environmental NGOs can promote the development and diffusion of common international norms and country commitments on environmental reporting, green budgeting, and the integration of the environment into medium term government strategy setting. GIFT, as a multi-stakeholder network, is well-placed to promote a role for national CSOs in norm development and in assessing the quality of environmental governance in their countries.

Taken together, the proposals illustrated in Figure 1 are obviously ambitious. They are intended to suggest the type of comprehensive framework needed to guide a series of progressive steps towards better environmental stewardship, phased in depending on starting points and national priorities. The proposals reflect the call in SDG 16 for accountable and transparent institutions that ensure public access to information and inclusive decision making. The capacity for national environmental monitoring and reporting comprises core infrastructure for sustainable development, and for measuring achievement of a number of the SDGs, many of which are high level aggregate outcomes that must be measured by in-country environmental monitoring systems. This requires progressive capacity building consistent with SDG 17.

Comprehensive application to environmental stewardship of the tools of mandatory transparent target setting and systematic independent reporting, and green budgeting, may well be key changes required if we are to begin to turn around the potentially cataclysmic decline in the state of the environment. It is only thirty years ago that few would have ever imagined that many sovereign governments would pass laws obliging themselves to fiscal transparency and fiscal responsibility or to setting inflation targets with delegation of monetary policy implementation to independent central banks.

Today we urgently need a similar leap of imagination, and crucially also of citizen demands and engagement, and of political leadership, to protect the natural environment for future generations.