Some public programs are designed as the result of the political realm, besides any possible technical propositions and considerations. Pork barrel funds are a reality, in developing countries, as well as in developed ones. This was the case of the Metropolitan Development Fund in Mexico.

The fund started before 2011 changing forms and structure but, continued growing throughout the years during the approval phase of the budget cycle. In Mexico, a presidential system, each year the executive power, through the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (MoF), presents to Congress the budget proposal for the next fiscal year, which is then analyzed, amended and finally approved. Year after year, this program returned from the legislative in the approval phase of the budget process with significantly more resources than proposed by the executive branch, as a result of political negotiations, to the point of being implemented during the fiscal year in projects unlinked to the development and sectoral priorities. Organizations and researchers started noting the lack of a clear objective and inefficient allocation of these resources, resulting in the financing of projects that encouraged the use of private transport, rather than more sustainable cities (see for example the The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) of Mexico report Diagnosis of federal funds for transportation and urban accessibility: How we spend our resources in Mexico in 2011 by Javier Garduño ). Furthermore, organizations trying to engage and study the effects of such resources encountered significant problems in following the money. In 2013-2014, the legislative management of this fund, finally led to a big scandal involving congress members engaging in corruption to include and approve projects in such fund.

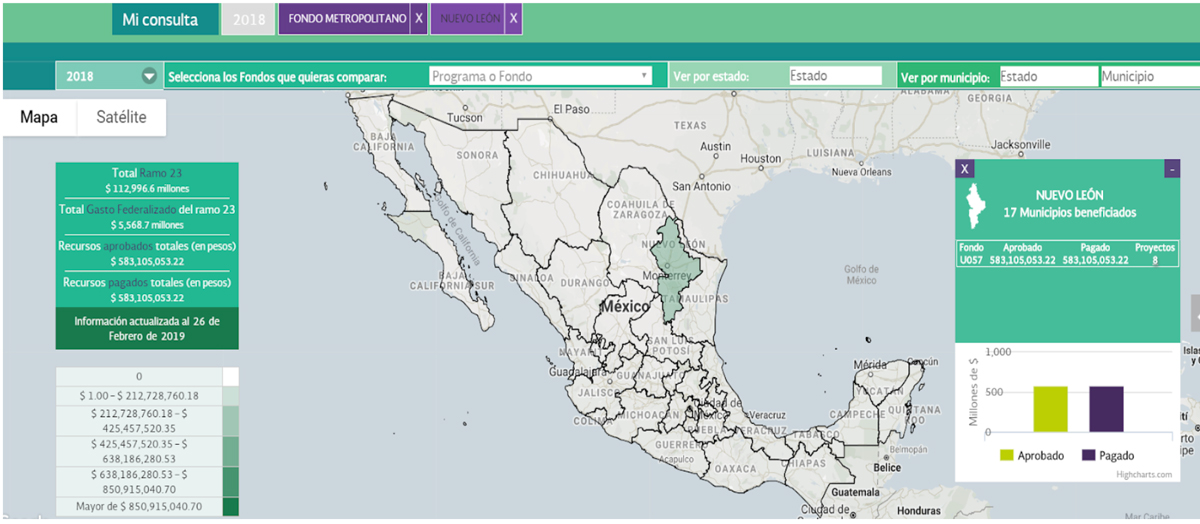

Before public opinion, it is usually hard to separate different levels of government when such scandals arise, as the public condemn politicians as a whole.  Therefore, the MoF decided to take action through fiscal transparency, so the public could distinguish the process and its outcomes. While it might not be the most obvious solution, it was a form of clarifying that although the MoF managed the delivery of the funds, it was not taking part of the corruption and was taking actions to expose it, as a way to tackle it. With such goals, in 2014 the MoF presented a platform publishing the details of the approved projects expecting the public to be able to monitor approval and implementation. As the Mexican MoF was a member of GIFT, the network was part of the public launch of these changes, highlighting the importance of such actions to lead to public participation and social impact.

Therefore, the MoF decided to take action through fiscal transparency, so the public could distinguish the process and its outcomes. While it might not be the most obvious solution, it was a form of clarifying that although the MoF managed the delivery of the funds, it was not taking part of the corruption and was taking actions to expose it, as a way to tackle it. With such goals, in 2014 the MoF presented a platform publishing the details of the approved projects expecting the public to be able to monitor approval and implementation. As the Mexican MoF was a member of GIFT, the network was part of the public launch of these changes, highlighting the importance of such actions to lead to public participation and social impact.

Conversation shifted to discuss in depth the approval of the projects and what needed to be changed in the design of the fund to achieve sustainable cities. With the data available, civil society organizations such as the Urban Cycling Network (BICIRED) and ITDP were able to engage in the approval process of the budget cycle with an informed social media campaign (money for the humane city- a catchy phrase in Spanish Lana para la Ciudad Humana ) and lobbying actions for the 2015 budget. That year, the approved Budget Decree included a new clause, stating that the Metropolitan Development Fund should consider non-motorized mobility to finally include in subsequent years that at least 15% of resources should be directed to public transport and non-motorized mobility.

Conversation shifted to discuss in depth the approval of the projects and what needed to be changed in the design of the fund to achieve sustainable cities. With the data available, civil society organizations such as the Urban Cycling Network (BICIRED) and ITDP were able to engage in the approval process of the budget cycle with an informed social media campaign (money for the humane city- a catchy phrase in Spanish Lana para la Ciudad Humana ) and lobbying actions for the 2015 budget. That year, the approved Budget Decree included a new clause, stating that the Metropolitan Development Fund should consider non-motorized mobility to finally include in subsequent years that at least 15% of resources should be directed to public transport and non-motorized mobility.

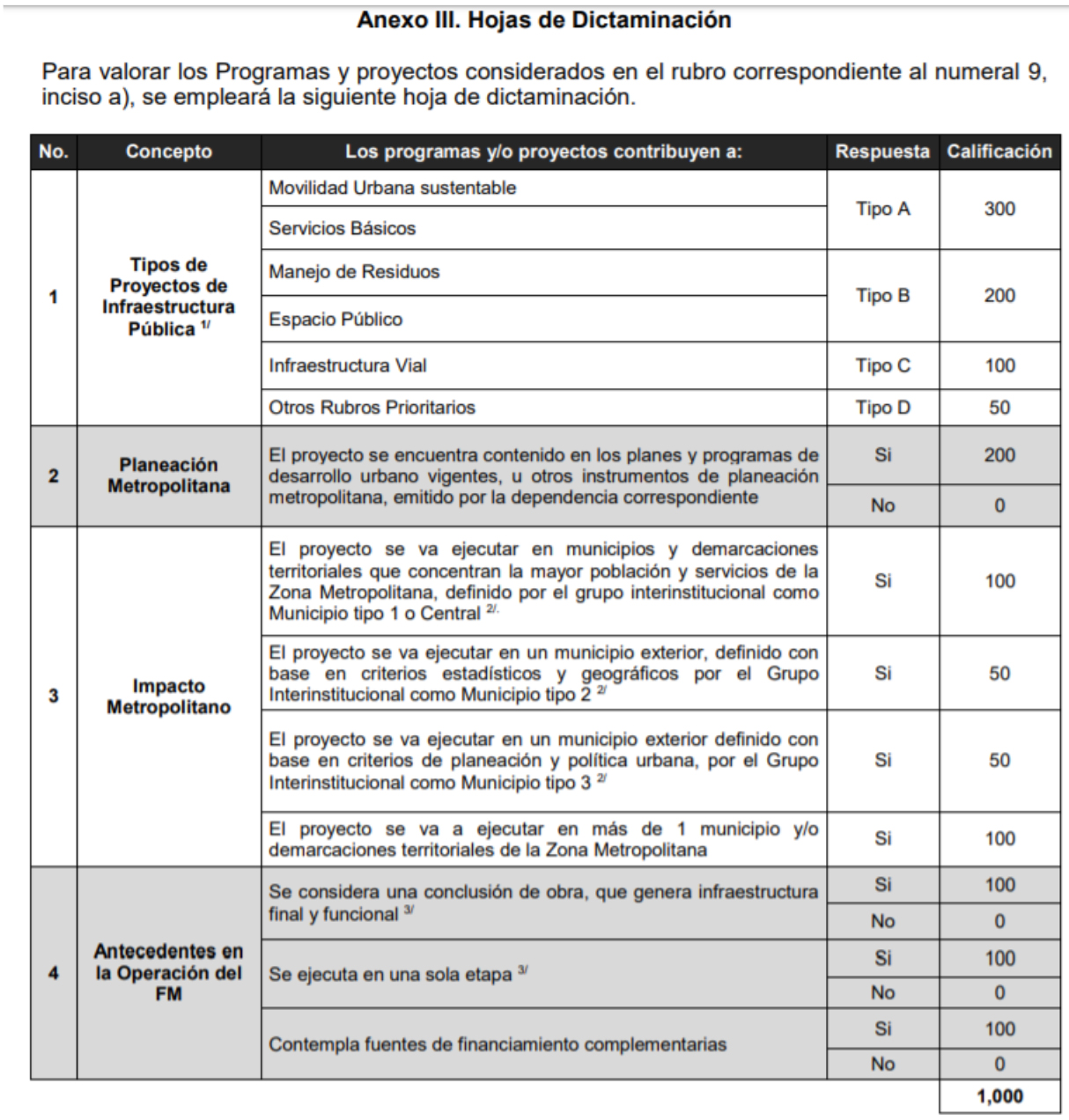

In 2017 a complete redesign of the program was possible with some milestones achieved by different ministries and with the findings of an external evaluation to the program. For the 2018 fiscal year the operating rules of the program changed completely, creating a collegiate body to approve the projects, conformed by the MoF, the Ministry of Territory and Urban Development and the Ministry of Environment. The approval of the projects would now require better pre-investment studies, depending on the cost of the project a cost-benefit evaluation or others, and an opinion sheet filled out by the collegiate body, highly focused on awarding points to sustainability, urban mobility and resilience projects.

In 2017 a complete redesign of the program was possible with some milestones achieved by different ministries and with the findings of an external evaluation to the program. For the 2018 fiscal year the operating rules of the program changed completely, creating a collegiate body to approve the projects, conformed by the MoF, the Ministry of Territory and Urban Development and the Ministry of Environment. The approval of the projects would now require better pre-investment studies, depending on the cost of the project a cost-benefit evaluation or others, and an opinion sheet filled out by the collegiate body, highly focused on awarding points to sustainability, urban mobility and resilience projects.

Cutting with inertia of how projects are presented is not easy and therefore a more paused approval of spending happened, but slowly more of the expected projects started to flow from the local governments to the MoF.

This case reflects how opening spending data can lead to changing relations among different powers in government (executive, legislative, audit and national-local governments); it can improve the quality of the discussion between civil society and government (when the government is open to listen and act!), highlighting that it is not always organizations expert in public finances that can induce results from fiscal transparency; and finally it can lead to more effective public spending. As such, fiscal transparency and public participation triggered policy changes that replaced the previous pork barrel system in favor of better public spending through policies for sustainable development.