Direct engagement between citizens and governments is increasingly recognized as a critical link in the chain between fiscal transparency, more effective accountability for public financial management, and better fiscal and development outcomes. The importance attached to public participation reflects the acceptance that citizens and civil society organisations are important agents of good governance and sustainable development, alongside markets and the state.

So, what is public participation in fiscal policy?

Public participation in fiscal policy refers to the variety of ways in which the public “ including citizens, civil society organizations, community groups, business organizations, academics, and other non-state actors “ interact directly with public authorities on fiscal policy design and implementation The participation may be invited by an official entity, such as a ministry of finance, line ministry or agency, a legislature, or a Supreme Audit Institution. Participation may also be ˜invented’ “ initiated by a non-state actor. In either case, public participation as advocated here is intended to be open and to stand in sharp contrast to back-room lobbying that risks subverting the public interest to private interests.

While people often think of public participation in fiscal policy as being about the annual budget, it is much broader than this, encompassing engagement in four main domains:

- Across the whole annual budget cycle, from budget preparation, legislative approval, budget implementation, and review and audit.

- In new policy initiatives or reviews (e.g. on revenues or expenditures) that extend over a longer period than the window for preparation of the annual budget.

- In the design, production and delivery of public goods and services.

- In the planning, appraisal, and implementation of public investment projects.

Public participation covers both macro-fiscal policy “ the main fiscal aggregates, the appropriate size of the deficit and so on “ as well as more micro issues of tax design and administration, and the allocation and effectiveness of spending.

Participation in fiscal policies may be through face to face communication, deliberation or input to decision-making, through written forms of communication including via the internet, or by combinations of different mechanisms. It ranges from one-off public consultation or invitations for submissions, to on-going and institutionalized relationships, such as regular public surveys, standing advisory bodies, or administrative review mechanisms. Participation can be through broad-based public engagement as well as deliberations involving experts, or combinations of the two. It could potentially include ˜participatory budgeting’ “ where citizens vote on and decide how a specific line in the budget will actually be spent “ although, the Philippines aside, this has generally only been implemented at sub-national government level, and public participation in fiscal policy refers to a much wider range of practices.

To make the right to public participation more practical and meaningful, the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (GIFT) has implemented a multi-year work program to generate greater knowledge about country practices and innovations in citizen engagement. Outputs include country case studies, a set of Principles of Public Participation in Fiscal Policy, a Guide on Public Participation, and instruments to measure public participation in fiscal policy.

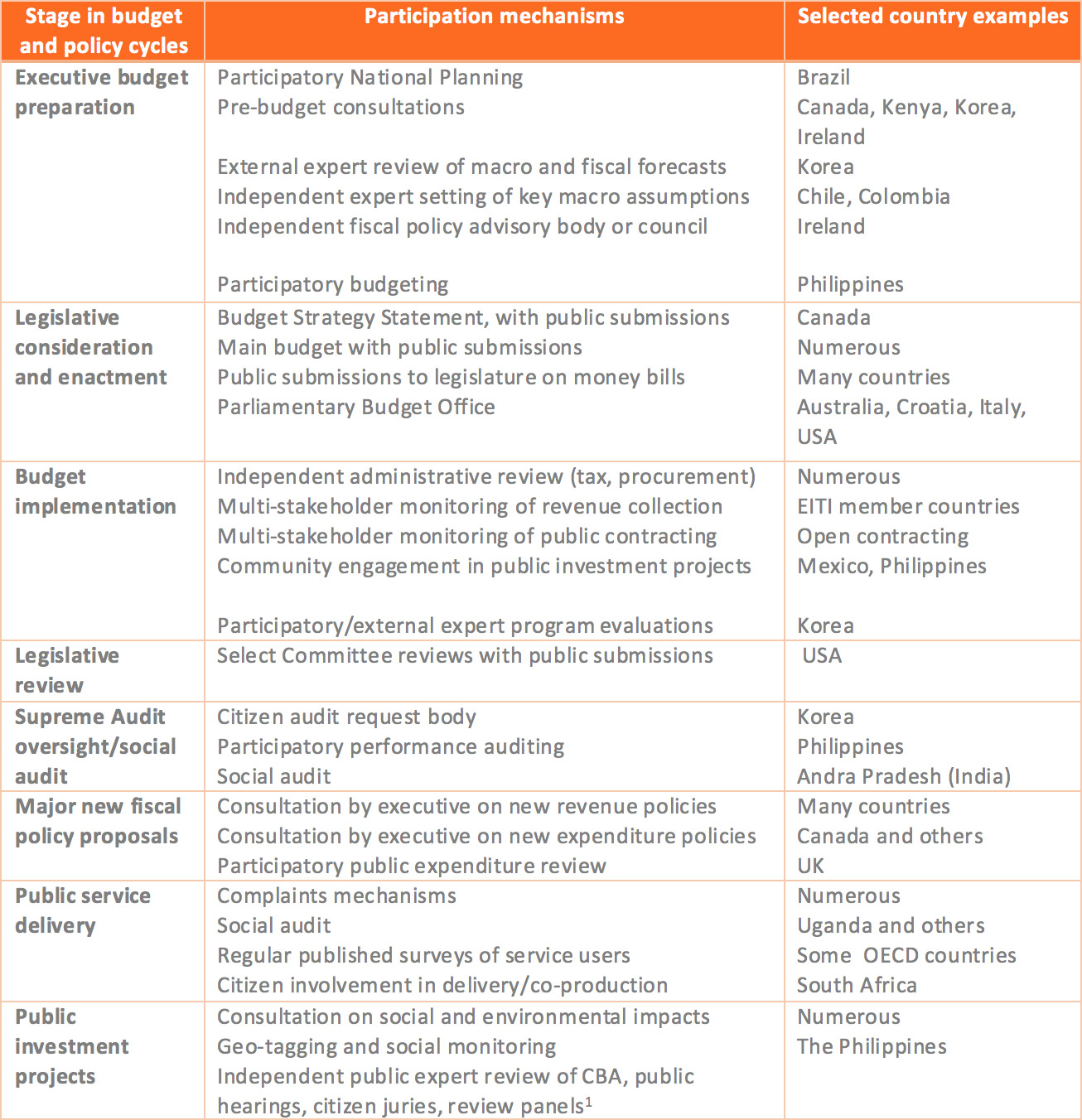

Table 1 sets out selected examples of public participation in fiscal policy, to illustrate the broad range of mechanisms. Details of many of these mechanisms are available in the GIFT Participation Guide.

Table 1: Selected examples of public participation in national fiscal policy by stage of budget and policy cycles

1. As advocated for example by Flyvberg, Holm and Buhl (2004) to counter optimism bias in the appraisal of large infrastructure projects.

1. As advocated for example by Flyvberg, Holm and Buhl (2004) to counter optimism bias in the appraisal of large infrastructure projects.

Where did the recent push for increased public participation in fiscal policy come from?

Starting with the IMF’s 1998 Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency, the first generation of international fiscal transparency standards focused on the need for comprehensive disclosure of fiscal information. More recently, open fiscal data developments are greatly expanding the scope of information available publicly. Experience has shown, however, that disclosure is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for accountability. Attention has recently moved to translating public disclosure into more effective accountability by means of greater public engagement on fiscal management, greatly facilitated by developments in ICT. Reflecting these developments, Principle Ten of the 2012 GIFT High Level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation, and Accountability established that: ˜Citizens and non-state actors should have the right and effective opportunities to participate directly in public debate and discussion over the design and implementation of fiscal policies.’ This reflected the view of GIFT’s Lead Stewards “ including the IMF, the World Bank, and the International Budget Partnership “ following the GFC, that public participation is a potential game-changer: participation could, over time, fundamentally strengthen accountability, and improve the fairness, legitimacy, effectiveness, and sustainability of fiscal policies.

Requirements for public participation have since been incorporated in:

- The 2014 IMF Fiscal Transparency Code (principle 2.3.3),

- The OECD’s Principles of Budgetary Governance 2014 (Principle 5),

- Some PEFA indicators (PI-13 (iii) on the existence of a functioning tax appeals mechanism, PI-18.2 on legislative review of the budget, and PI-24.4 on procurement complaints mechanism),

- The forthcoming OECD-GIFT G20 Budget Transparency Toolkit (Section 4, Openness and Civic Engagement).[1]

The 2017 Open Budget Survey includes an expanded section on public participation by the executive, the legislature, and the Supreme Audit Institution, and will provide a detailed source of information on practices in the 115 countries covered by the survey.

Public participation in public policy generally is a key element of the Open Government Partnership, a multilateral initiative launched in 2011 in which 75 governments have made specific commitments to develop and implement action plans to increase transparency and public engagement in collaboration with and monitored by civil society. One of the OGP’s working groups, the Fiscal Openness Working Group, brings together ministries of finance and civil society organisations to promote peer learning and more ambitious fiscal openness commitments.[2]

Public participation is also key to some of the Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 5 (gender equality), Goal 10 (reducing inequality), and Goal 16 (Peace, justice and inclusive institutions), while enabling public participation throughout the budget process is reflected in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and Financing for Development Resolutions.

More recently, the World Bank’s World Development Report 2017 stressed the potential of participatory processes to increase the contestability of policy design and implementation, leading to higher levels of legitimacy and cooperation and more equitable policies[3].

What is the evidence supporting positive impacts from public participation?

While there is a significant body of empirical evidence supporting a plausible causal link between the disclosure of fiscal information and fiscal (and to a much lesser extent) development outcomes, at this stage rigorous evidence on the impacts of public participation is more limited. It is essentially confined to sub-national government, particularly to participatory budgeting in Brazil but more recently also to other types of participatory interventions in a number of mainly developing and middle income countries (e.g. India, Indonesia, Afghanistan, Mexico, Peru, USA). In a systematic review of the rigorous empirical literature on fiscal transparency and participation, de Renzio and Wehner find that there is strong evidence linking different types of participatory mechanisms in budget processes to shifts in resource allocations (increased share of social sector spending corresponding to citizen preferences) and to improvements in public service delivery. In Ghana, where businesses are involved in the design of tax policies, they are more likely to pay their taxes (World Development Report 2017). Wampler, Touchton, and Borgues, in a study of 5,550 Brazilian municipalities over the period 2006-2013, find a strong and positive relationship between the presence of participatory institutions and improvements in infant mortality, and that participatory institutions, social programs, and local capacity reinforce one another to improve well-being.

While, as noted, this evidence is at sub-national level, the underlying causal mechanisms “ increased contestability of fiscal policy design and implementation, a reduction in elite influence, and more effective accountability “ are the same as for the central government-level mechanisms outlined in Table 1. The challenge now is to undertake research at the national level to test the effectiveness of different types of participation mechanisms implemented in different ways.

Possible objections to increased public participation in fiscal policy, and responses

While direct public engagement in budgeting has fairly rapidly become established as an international norm, it is worth considering possible objections to it, which include:

- Public participation is costly: but the ICT revolution has dramatically cut the cost of direct engagement with citizens, and created completely new possibilities for interactions. Public participation is a means for government to tap into the information, insights and perspectives distributed throughout society, potentially lowering the cost and improving the effectiveness of official research, policy development, service delivery, monitoring, review, and evaluation. Some ministries of finance e.g. in South Africa, Mexico, are pursuing increased public participation to promote improved performance by line ministries in delivery public services and implementing public investment projects. In addition, proportionality is one of the GIFT Participation Principles, recognizing the need to tailor participation exercises to the size and importance of the issue concerned.

- Direct public engagement could undermine the role of existing decision making and accountability structures, including the legislature in representative democracies: but direct public participation is designed to add to, complement, and strengthen existing governance arrangements – and increase trust in government – not to set up parallel processes. Calling for public submissions during consideration of money bills is a long-standing and widespread practice that illustrates well the complementarity between direct public participation and legislative oversight.

- Fiscal policy is too complicated for the general public, and should be left to the experts: but open engagement of external experts is one of the participation mechanisms proposed. In addition, fiscal policy involves ethical and distributional choices that should not be the sole preserve of ˜experts’, it is inherently political and will not be left to experts in any case.

- There is a culture and long-standing practice of budget secrecy: but policy making in general has become much more open over the last few decades, and budget secrecy can be retained in the narrow range of cases where pre-disclosure could result in adverse behavioural response.

- Public engagement takes time, and slows down the policy process: but participation is a citizen right, similar to and complementary to the right to information. In addition, it can help improve policy quality, avoid policy reversals, and thereby save time and cost.

- Public engagement exercises can be dominated by more influential or well-placed groups and individuals at the expense of the poor and marginalised. This is a real risk “ although the counterfactual is continued traditional policy development and implementation that may often be captured by very narrow elites. The GIFT Participation Principles emphasize efforts to ensure a diversity of inputs, including from traditionally excluded voices, and how public engagements are conducted in practice will directly influence how diverse the inputs are. For instance, evidence from randomised controlled trials of community interventions in Afghanistan and Indonesia has found that elite preferences are less likely to dominate where decisions on local project selection are taken by secret voting rather than in open local council meetings.[4]

Where to next?

Direct public participation has emerged as an important new international norm on how governments and other state entities should manage and oversee fiscal policy. GIFT will continue to support the implementation of this norm through extending and deepening the Guide on Public Participation, gathering more evidence of country practices, what works, and the impacts of different types of participation mechanisms, and supporting assessments of public participation against the various international instruments in which the norm is now embedded. We would be pleased to receive additional country examples of effective public engagement for inclusion in the Guide “ and in fact we are offering prizes for compelling stories of viable approaches to public engagement in central government fiscal policy submitted by 25 August 2017 (see https://fiscaltransparency.net/giftaward/). GIFT’s work program will also focus on connecting public participation initiatives more closely to the lives of ordinary citizens, by opening up the links between national budgets, public engagement, and the delivery of local public services such as education and health care, and by increasing the effectiveness of fiscal transparency and public engagement in countering corruption.

Murray Petrie

Lead Technical Advisor

GIFT

[1] In addition, GIFT has developed an indicator measuring public participation in fiscal policy that is being piloted as a voluntary supplement in a PEFA assessment

[2] See https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/working-groups/fiscal-openness

[3] http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2017

[4] De Renzio and Wehner, 2017.