This post is the second in a short series that GIFT will be running to provide ideas for the 51 member countries currently preparing their next Action Plans. The first post discussed the steps OGP countries should take in their next Action Plans to increase fiscal transparency and participation. A third post will look at how well countries have implemented the OGP commitments on fiscal transparency in their first Action Plans. The posts draw on a series of GIFT papers, ˜Fiscal Transparency in Open Government Partnership Countries, and the Implementation of OGP Commitments: An Analysis‘, prepared for successive meetings of the OGP-Fiscal Openness Working Group, and on GIFT case studies of public participation in fiscal policy.

So how open are budgets in OGP member countries?

In summary, there are some outstanding examples amongst OGP countries of rapid increases in fiscal transparency in recent years, although the average score and pace of improvement are low, and some OGP countries have gone backwards. It is notable that many of the rapid gains came from publication of documents that governments were already producing for their internal use and for donors, but not making publicly available.

The best way to measure budget transparency is to draw on data from the Open Budget Survey (OBS) compiled by the International Budget Partnership (IBP) and used to compile country scores on the Open Budget Index (OBI). The OBS is the most comprehensive cross-country data on current practices with respect to fiscal transparency.[1] There have been five OBS surveys since 2006, with country coverage increasing from 59 countries in 2006 to 102 countries in 2015. The OBS is also the source of data on whether a country meets the minimum entry requirements for budget transparency for the OGP – which are the publication of the Executive’s Budget Proposal and the Audit Report.

So what does the Open Budget Survey tell us?

First, 29 of the 47 OGP countries are categorized in the OBI as providing insufficient budget information to the public. These 29 OGP members scored 60 or below in the 2015 OBS. Four of those countries provide minimal budget information, the second lowest category. In terms of OGP regions, average OBI scores were as follows: Africa 55; Asia 62; Europe 59; the Americas 58.

Second, on average, the pace of improvement in budget transparency is slow. Across all OGP countries in the Survey there was an average increase of only +2 on the OBI between the 2012 and 2015 surveys – which is lower than the +3 improvement on average for all countries in the OBS.

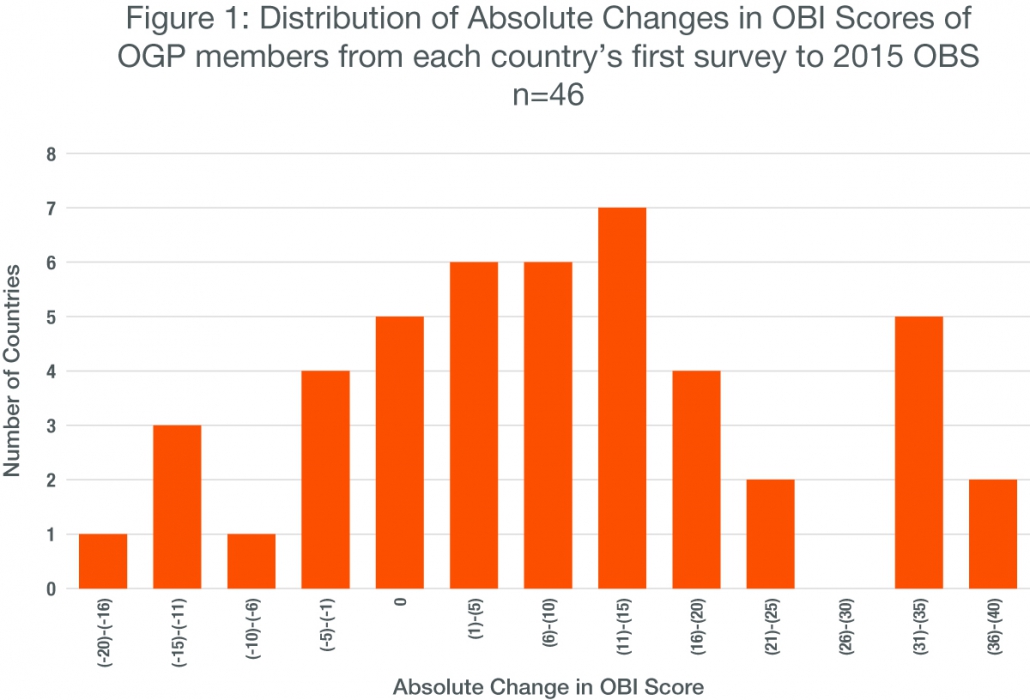

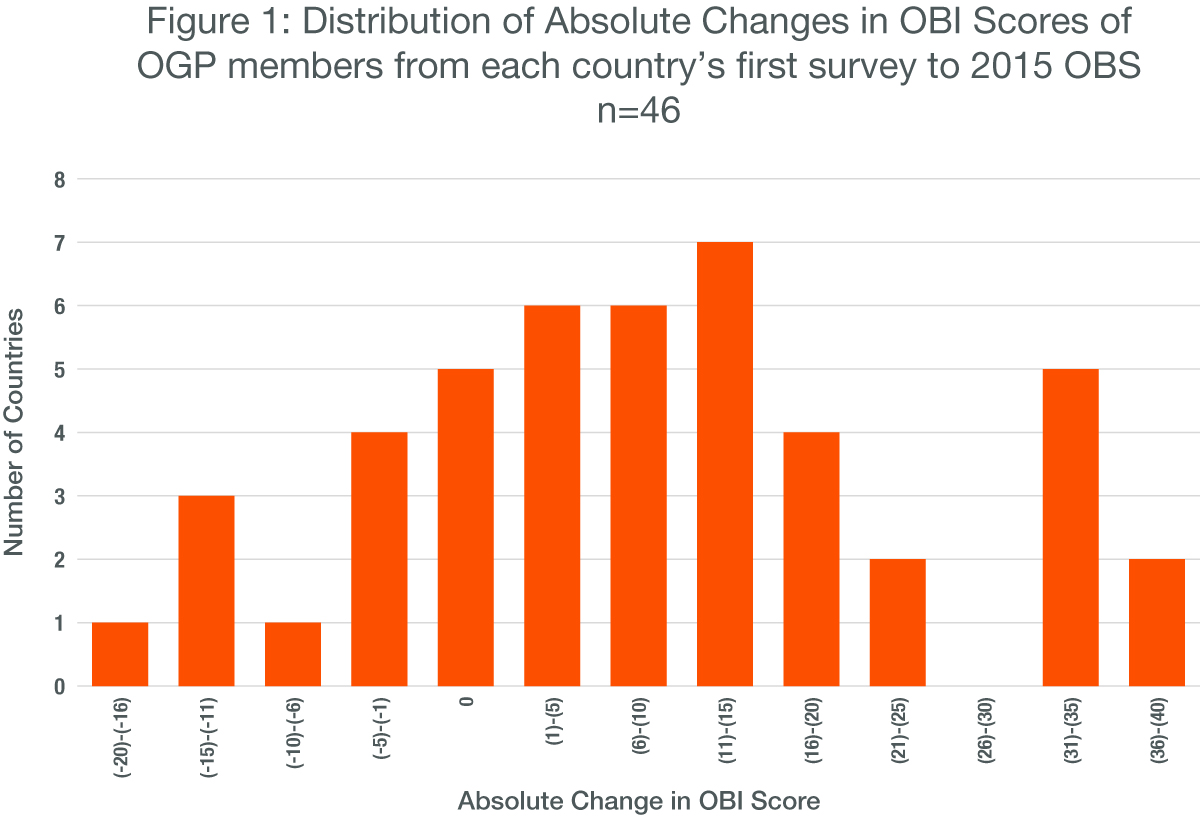

Third, progress is very uneven across OGP members. Figure 1 shows the distribution of absolute changes in OGP member country scores from each country’s first inclusion in the OBS to the 2015 survey, by size of change and number of countries.

Fourth, there are some outstanding examples amongst OGP countries of rapid increases in fiscal transparency. The maximum possible score on the OBI is 100, so the following increases in scores (drawn from the same data as in Figure 1) represent major step-increases in the level of budget transparency.

- In Africa: Malawi +37; Liberia +35;

- In the Americas: Honduras +31; Dominican Republic +39; El Salvador +25;

- In Asia: Mongolia +33; Azerbaijan +21; Indonesia +17;

- In Europe: Georgia +32; Tunisia +31; Bulgaria +18; Albania +13; Croatia +11.

Fifth, there are also some notable examples of backsliding on fiscal transparency amongst OGP members in the most recent period. Notable reductions in OBI scores (falls of 10 or more on the OBI between the 2012 and 2015 surveys) include: United Kingdom (-13), Korea (-10), Slovak Republic (-10), and Honduras (-10). And there are four OGP members that, in the 2015 OBS did not meet the minimum fiscal transparency eligibility criteria for OGP membership in terms of the availability of the Audit Report: Malawi, Tunisia, Liberia, and Spain.

The OGP member with the greatest improvement between the 2012 OBS and 2015 OBS was Tunisia, which increased its score by 31 points by publishing the Executive’s Budget Proposal and Citizens Budget. Romania (+28) and the Dominican Republic (+22) both saw substantial improvements to their OBI score by improving the comprehensiveness of the Executive’s Budget Proposal. Peru, the Philippines, Sierra Leone, Italy, Malawi, Georgia, and El Salvador all improved by 10 points or more.

How well do OGP countries score on public participation in budgeting, and on the strength of legislative oversight?

The average public engagement score in 2015 for all 102 countries surveyed was only 25 out of 100, while for OGP member countries the average was 36. This means that OGP members are significantly more open than non-members, on average. However, in absolute terms a score or 36 means that on average OGP countries included in the OBS only provide weak opportunities for the public to participate in the budget process.

Table 1 shows the average participation scores by OGP region for OGP members.

The stand out performer on public participation across all 102 countries in the 2015 OBS was South Korea, with a score of 83. This is in sharp contrast to Korea’s record of public consultation in developing and implementing its first and second OGP Action Plans. The IRM reports for this country found that it was unclear how, if at all, the government engaged the public in the development or implementation of the Action Plans.

Other OGP members that scored above 60 for public participation in the 2015 Survey were Norway (75), Brazil (71), USA (69), the Philippines (67), South Africa (65), and New Zealand (65).

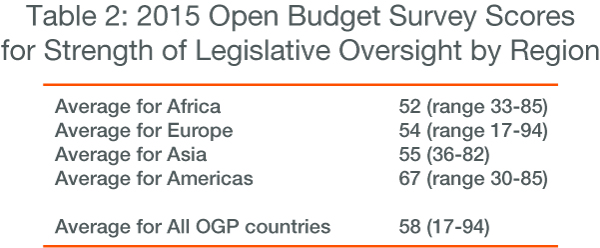

With respect to the strength of legislative oversight, there is a very wide range of scores across countries, although, as illustrated in Table 2 below, there is limited regional variation.

Notable findings with respect to legislative oversight are that 19 OGP countries (40% of all OGP members) do not have a specialized budget research office attached to the legislature, and in 22 OGP countries (47%) there was a weak or no quality assurance system for audits.

So what steps should OGP countries take in their next Action Plans to increase fiscal transparency and participation?

As noted, many of the rapid increases in OBI scores achieved by a number of OGP members in recent years have come from publication of budget documents that were already produced for internal use and for donors, but were not being made available to the public. Simply deciding to publish such reports and documents would be a very effective and low-cost step that many countries should consider to rapidly increase transparency. The first post in this series looked in-depth at this and other specific actions that OGP members should be considering now to increase transparency and public participation in budgeting in their next Action Plans. The final post in this series will analyse how well countries implemented the fiscal openness commitments in their first Action Plans.

Murray Petrie

GIFT Lead Technical Advisor

[1] See ˜Defining the Technical Content of Global Norms: Synthesis and Analytic Review Revised Phase 1 Report for the GIFT Advancing Global Norms Working Group. https://fiscaltransparency.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/GIFT-Defining-the-Technical-Content-of-Global-Norms-Synthesis-and-Analytic-Review.pdf