The Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency was formed in 2011 as an action network to launch a reinvigorated campaign for improvements in fiscal transparency, by bringing a wider range of stakeholders together around a broadened and stronger set of standards and activities. GIFT’s overall objective is to promote more effective fiscal policies that make a stronger contribution to economic, social and environmental outcomes.

The GIFT High-Level Principles were published in 2012 to guide policy makers and all other stakeholders in their efforts to increase the transparency of taxation and public spending openness, and to help promote improvements in the coverage, consistency and coherence of the existing standards and norms for fiscal transparency. The Principles have played an important role in promoting convergence in standards and in identifying gaps and deficiencies, and continue to be central in framing the activities of the network. For instance, High-Level Principle 10, asserting a citizen right to direct participation in fiscal policy, was the origin of GIFT’s significant on-going work promoting more direct public engagement in the design and implementation of fiscal policies.

The Expanded Version of the High-Level Principles, explains each of the ten Principles in more detail, contains up to date country examples of good practices, and provides additional information and sources of guidance for those applying the Principles in practice. We hope that any policy maker or practitioner interested in implementing the high level principles in their country would see a practical and resourceful benefit from this explained and illustrated version of the principles.

Since 2014, most of the normative instruments of the fiscal transparency global architecture have been revised and updated, including the IMF Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency, OECD instruments, the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability framework, the International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Survey and the IMF Manual on Government Finance Statistics. The OECD has also produced the Tool Kit on Budget Transparency. At the same time, many governments have strongly engaged in advancing fiscal transparency and public engagement in fiscal processes. Therefore, this version takes into account these changes and includes new references and practices to illustrate each of the principles.

As is the case in all of GIFT’s work, this document is a collective effort of the network. But it would not have seen the light without the leadership, time and persistence of Murray Petrie, GIFT’s Lead Technical Adviser. Jon Shields and Tim Irwin deserve also special credit for their contributions. Finally, Tarick Gracida, GIFT Technology and Communications Coordinator, was in charge of designing and producing this friendly and accessible version that the reader has before them.

The Expanded Version of the Principles is intended to be a live document. It aims to provide practical support to champions who want to engage and continue pushing the fiscal transparency, accountability and participation agendas in their countries. The effort would only be worth the time and resources involved if the document is used, and therefore questioned, discussed, enriched, and challenged again. As such, your suggestions for additions, corrections or improvements are therefore a crucial component of this effort. We thank you in advance for joining us in this journey.

Juan Pablo Guerrero

Network DirectorI. Introduction

a. The purpose of the Expanded Version b. The structure of the documentII. The formation of GIFT and the role of the High-Level Principles

III. Mapping of current international fiscal transparency standards and norms

IV. Guide to the GIFT High-Level Principles

i. A citizen right to fiscal information ii. Reporting on aggregate fiscal policy iii. High quality information on past, present, and forecast fiscal activities iv. Information on objectives, outputs and outcomes v. The rule of law in public financial management vi. Relationships between government and the private sector vii. Clarity of roles within and between branches and levels of government viii. Legislative oversight ix. The role of the Supreme Audit Institution x. A citizen right to direct public participation in fiscal policy

Glossary of terms

Tables Table 1 Key elements of the core international fiscal transparency instruments Table 2 The relationship between disclosure and public participation scores in the 2015 OBS Table 3 Examples of Public Participation in National Fiscal Policy

Figures Figure 1 The GIFT Theory of Change Figure 2 The Hierarchy of High-Level Principles, standards, and assessments Figure 3 Mapping current international fiscal transparency instruments

Boxes Box 1 The GIFT High-Level Principles Box 2 The United Nations General Assembly Resolution on Fiscal Transparency Box 3 Global SAI Performance at a Glance

Annexes

Annex 1: The full text of the GIFT High-Level PrinciplesCSO Civil society organisation

EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

FOWG Fiscal Openness Working Group

FTC Fiscal Transparency Code (IMF)

GFSM Government Finance Statistics Manual

IBP International Budget Partnership

ICT Information and communications technology

IFAC International Federation of Accountants

IMF International Monetary Fund

INTOSAI International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions

IPSAS International Public Sector Accounting Standards

IPSASB International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board

OBI Open Budget Index

OBS Open Budget Survey

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

OGP Open Government Partnership

PEFA Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability

SAI Supreme Audit Institution

SNA System of National Accounts (United Nations)

TADAT Tax Administration Diagnostic Tool

a) The purpose of the Expanded Version

The Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency was formed in 2011 as an action network to launch a reinvigorated campaign for improvements in fiscal transparency, by bringing a wider range of stakeholders together around a broadened and stronger set of standards and activities.

One of the network’s first initiatives was to review the plethora of international standards and norms on fiscal transparency for comprehensiveness and consistency. This prompted the development in 2012 of the High-Level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation and Accountability, which were ‘…intended to guide policy makers and all other stakeholders in fiscal policy in their efforts to improve fiscal transparency, participation and accountability, and to help promote improvements in the coverage, consistency and coherence of the existing standards and norms for fiscal transparency.’

The purpose of this Expanded Version is to explain the role played by the GIFT High-Level Principles in promoting greater fiscal transparency globally, as well as to set out the relationship between each of the High-Level Principles and the corresponding standards, norms, assessments, and country practices to which they relate.

The Expanded Version should help readers to quickly gain an overview of the current multiplicity of instruments in relation to each other, to find effective entry points to the more detailed sources of information and guidance, and to consider where standards and assessments of practice may need strengthening to better realise the aspirations in the High-Level Principles.

The Expanded Version captures the major changes that have taken place over the last few years to international fiscal transparency standards and assessment tools, given that the main instruments have all been substantially revised since 2013. The completion of this document therefore comes at an opportune time, when the normative architecture seems likely to remain comparatively stable in the short to medium term.

In addition to information on fiscal transparency standards and norms, the Expanded Version contains information on country practices – cross-country data mainly from the Open Budget Survey, references to good practice in selected countries, and links to published reports assessing country practices. Together with the sources of further information and guidance, readers can use the Expanded Version as a starting point for further investigation into the full range of issues relating to fiscal transparency, public participation or accountability.

Readers interested in further overview information on fiscal transparency standards should also refer to the 2017 OECD Budget Transparency Toolkit: http://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/budget-transparency-toolkit.htm . The Toolkit, which was designed with the participation of the GIFT Network, provides an alternative way of navigating to the various global fiscal transparency institutions, standards, and guidance materials, by using a structure – developed by the OECD – based around five key institutional or sectoral areas.

The Toolkit and this Expanded Version of the GIFT High-Level Principles are complementary. They use different organizing frameworks to cover a similar body of international fiscal transparency instruments.

A distinct contribution of this document is to place the international architecture of fiscal transparency instruments in the context of the GIFT High-Level Principles that are increasingly being used to promote greater coherence and comprehensiveness across instruments. Through disseminating information on the background to and objectives of the High-Level Principles and their role in identifying gaps and promoting coherence, the aim is to promote the further strengthening of fiscal transparency instruments and their more effective implementation.

One particular area where this Expanded Version should prove helpful is with respect to the growing interest in public participation in fiscal policy, which is being described as ‘the next frontier in fiscal transparency’.[1] The first generation of international fiscal transparency reforms focused on the public disclosure of fiscal information. Experience has shown, however, that disclosure is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for accountability. Attention is now increasingly moving to translating disclosure into more effective accountability by means of greater public engagement on fiscal management.

High-Level Principe 10 was the first international fiscal transparency norm to assert that citizens have a right to direct public participation in the design and implementation of fiscal policies. Given the scarcity of relevant international instruments, GIFT embarked on a multi-year work program to document country practices, understand the factors driving participation reforms, develop new instruments to guide and to measure country practices, and release a dedicated Guide on Public Participation. Readers interested in this burgeoning field should find the section in this document on High-Level Principle 10 particularly helpful.

In summary, then, the intention is that the Expanded Version will help to stimulate more effective efforts to promote greater accountability for taxation and public spending, strengthen incentives on governments to manage public resources more openly, and contribute to better economic, social and environmental outcomes.

b) The structure of the Expanded Version

The Expanded Version explains each of the ten High-Level Principles in more detail, and provides additional information and sources of guidance for those seeking to apply the Principles in practice.

For each of the ten Principles the document sets out:

- Why the Principle is important.

- As necessary, definitions of key terms.

- How the Principle is reflected in existing international norms and standards.

- Selected country practices with respect to adhering to the Principle.

- Sources of further information and guidance.

- This document also contains a glossary of common terms.

The Expanded Version will be updated regularly. Suggestions for additions or improvements – such as additional examples of good country practices, further sources of useful guidance material, or new reports on assessments of country practices – should be sent to the GIFT Coordination Team at info@fiscaltransparency.net

For regular monthly updates on developments in fiscal transparency and public participation, subscribe to GIFT’s Newsletter: https://fiscaltransparency.net/news/

[1] Participation is the next transparency frontier for OGP by Krafchik and Guerrero, at blog

The Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency was formed in 2011 following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Its formation, initiated by the World Bank, the International Budget Partnership, the International Monetary Fund, and the governments of Brazil and Philippines, reflected a sense of urgency that the GFC had revealed fundamental weaknesses in the state of fiscal transparency and a lack of accountability for the management of public finances, particularly in advanced economies.[1]

GIFT’s founders were also concerned by the on-going failures in the governance of fiscal policy that continued to see opportunities squandered for economic and social development globally. For instance, the International Budget Partnership concluded: ‘Yet the Open Budget Survey 2012 finds that the state of budget transparency and accountability is generally dismal. Only a minority of governments publish significant budget information. Fewer still provide appropriate mechanisms for public participation, and independent oversight institutions frequently lack appropriate resources and leverage. A large number of countries have made no changes, or made only a few changes, to their budget systems in recent years and continue to provide insufficient information. Some countries are even headed in the wrong direction; their systems have become more closed.’[2]

GIFT’s formation was intended to launch a reinvigorated campaign for improvements in fiscal transparency by bringing a wider range of stakeholders together around a broadened and stronger set of standards and activities.[3] The goal was to connect country governments with international and national CSOs and with institutions providing technical assistance and support to Public Financial Management reform (the IMF and the World Bank). GIFT was created as an action network i.e. a forum for these different organizations to find and share solutions to challenges in fiscal transparency in order to ‘make things happen’.

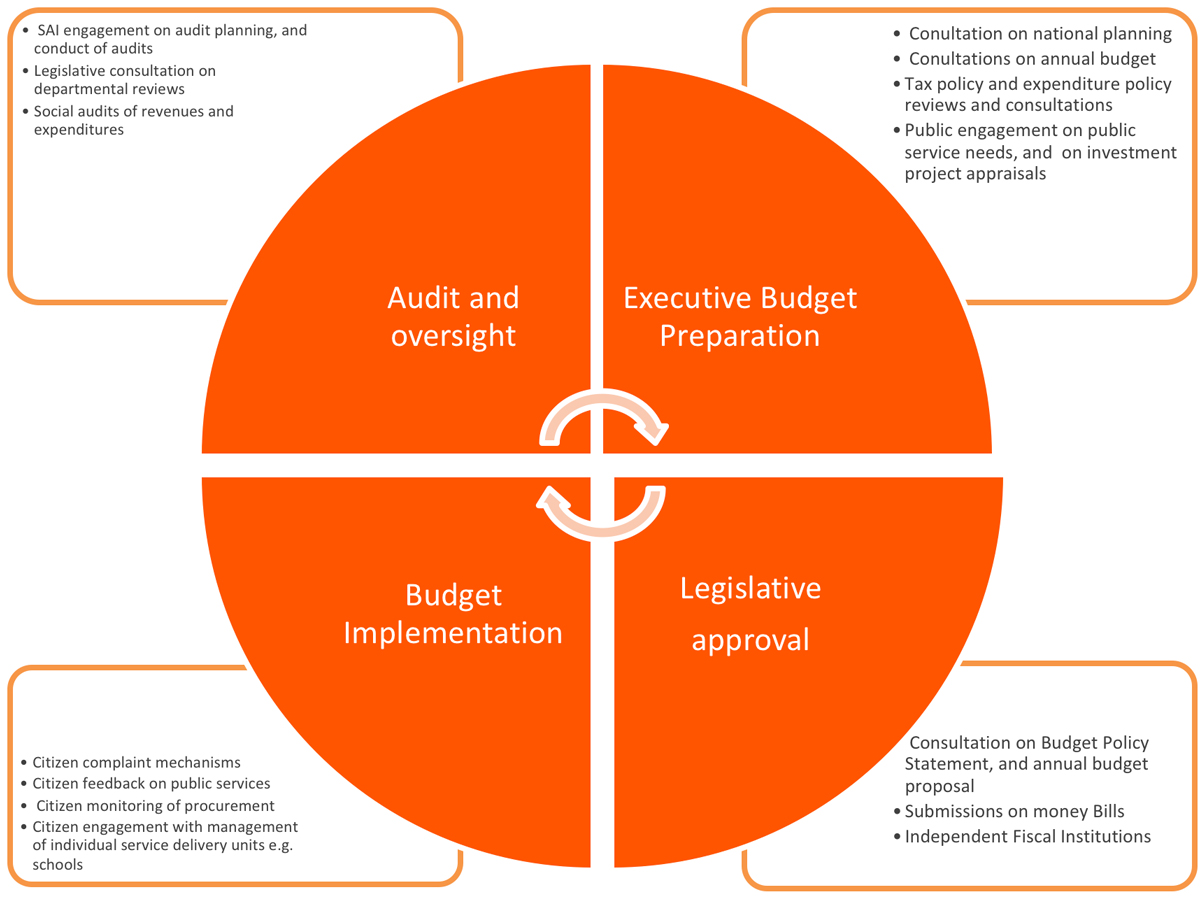

Figure 1 illustrates GIFT’s Theory of Change.

Figure 1. The GIFT Theory of Change

Based on this theory of change, GIFT’s work program has focused on four areas:

- Promoting convergence between, and increased coverage and coherence of international standards and norms on fiscal transparency, incorporating the rights of access to information and of direct public participation.

- Creating a forum to share experiences and good practices between CSOs, governments, experts, International Financial Institutions, and non-state funders.

- Strengthening incentives for reform by supplying research, evidence, and practical advice.

- Helping take advantage of technological advances to improve the accessibility and dissemination of budget and fiscal data, and to facilitate and leverage users’ feedback.

With respect to the norms workstream, one of GIFT’s first activities was to review the plethora of international standards and norms on fiscal transparency for comprehensiveness and consistency. The assessment found that, while the range of consensus had grown, significant gaps and inconsistencies remained.[4]

This prompted the development in 2012 of the GIFT High-Level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation and Accountability, which were intended to promote coherence and convergence across standards over time. The draft Principles were the subject of deliberation and discussion across the multi-stakeholder network, involving international standard-setters, national ministries of finance and related agencies from countries at different levels of development, and a range of international and national civil society organisations.

As such, the Principles reflect a shared set of norms that all GIFT’s stakeholders are committed to. They both frame and anchor the operationalization of the Principles in standards and norms, and instruments that assess practices.

As the preamble to the Principles stated, they were: ‘…intended to guide policy makers and all other stakeholders in fiscal policy in their efforts to improve fiscal transparency, participation and accountability, and to help promote improvements in the coverage, consistency and coherence of the existing standards and norms for fiscal transparency.’

The High-Level Principles are reproduced in Box 1. Principles 1-4 cover public access to fiscal information, while principles 5-10 concern the governance of fiscal policy.

Box 1: The GIFT High-Level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation and Accountability [5]

Principle 1: Everyone has the right to seek, receive and impart information on fiscal policies. To help guarantee this right, national legal systems should establish a clear presumption in favor of the public availability of fiscal information without discrimination. Exceptions should be limited in nature, clearly set out in the legal framework, and subject to challenge through low-cost, independent and timely review mechanisms.

Principle 2: Governments should publish clear and measurable objectives for aggregate fiscal policy, regularly report progress against them, and explain deviations from plans.

Principle 3: The public should be presented with high quality financial and non-financial information on past, present, and forecast fiscal activities, performance, fiscal risks, and public assets and liabilities. The presentation of fiscal information in budgets, fiscal reports, financial statements, and National Accounts should be an obligation of government, meet internationally-recognized standards, and should be consistent across the different types of reports or include an explanation and reconciliation of differences. Assurances are required of the integrity of fiscal data and information.

Principle 4: Governments should communicate the objectives they are pursuing and the outputs they are producing with the resources entrusted to them, and endeavor to assess and disclose the anticipated and actual social, economic and environmental outcomes.

Principle 5: All financial transactions of the public sector should have their basis in law. Laws, regulations and administrative procedures regulating public financial management should be available to the public, and their implementation should be subject to independent review.

Principle 6: The Government sector should be clearly defined and identified for the purposes of reporting, transparency, and accountability, and government financial relationships with the private sector should be disclosed, conducted in an open manner, and follow clear rules and procedures.

Principle 7: Roles and responsibilities for raising revenues, incurring liabilities, consuming resources, investing, and managing public resources should be clearly assigned in legislation between the three branches of government (the legislature, the executive and the judiciary), between national and each sub-national level of government, between the government sector and the rest of the public sector, and within the government sector itself.

Principle 8: The authority to raise taxes and incur expenditure on behalf of the public should be vested in the legislature. No government revenue should be raised or expenditure incurred or committed without the approval of the legislature through the budget or other legislation. The legislature should be provided with the authority, resources, and information required to effectively hold the executive to account for the use of public resources.

Principle 9: The Supreme Audit Institution should have statutory independence from the executive, and the mandate, access to information, and appropriate resources to audit and report publicly on the raising and commitment of public funds. It should operate in an independent, accountable and transparent manner.

Principle 10: Citizens should have the right and they, and all non-state actors, should have effective opportunities to participate directly in public debate and discussion over the design and implementation of fiscal policies.

The Principles are at a level of generality that can be applied across all countries, irrespective of constitutional arrangements, type or structure of government, variety of organisational arrangements and relationships, or level of development or capacity. They focus on functions rather than prescribing specific institutional forms. The standards, norms and assessment instruments above which the Principles sit are where graduated approaches are increasingly being developed to recognize diversity in country circumstances.

The High-Level Principles were the subject of a United Nations General Assembly Resolution in December 2012, sponsored by GIFT’s founding Lead Stewards: the Governments of Brazil and the Philippines, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the International Budget Partnership. UNGA Resolution 67/218 endorsed the GIFT Principles of fiscal transparency, participation and accountability and encouraged efforts by states and the UN system to help build state capacity for fiscal openness.

Box 2 contains the text of the Resolution, which represents an important endorsement by the international community of the GIFT Principles and of the intensified efforts to increase the development impacts of government taxation and spending. [6]

Box 2: UNGA Resolution 67/218: Promoting transparency, participation and accountability in fiscal policies

Recalling its resolution 66/209 of 22 December 2011 and its previous resolutions on public administration and development,

Recalling also the United Nations Millennium Declaration,

Acknowledging that fiscal policies have a critical impact on economic, social and environmental outcomes in all countries at all levels of development,

Emphasizing the need to improve the quality, efficiency and effectiveness of fiscal policies,

Recognizing the critical role that transparency, participation and accountability in fiscal policies can play in pursuit of financial stability, poverty reduction, equitable economic growth and the achievement of sustainable development,

Recognizing also that transparency, participation and accountability in fiscal policies should be promoted in a manner that is consistent with diverse country circumstances and national legislation,

1. Takes note of the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency and its High-level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation and Accountability of 2012;

2. Encourages Member States to intensify efforts to enhance transparency, participation and accountability in fiscal policies, including through the consideration of the principles set out by the Initiative, on a voluntary basis;

3. Also encourages Member States, in this regard, to promote discussions on advancing the common goal of transparent, participatory and accountable management of fiscal policies;

4. Invites Member States and relevant United Nations institutions to promote cooperation and information-sharing among all stakeholders to assist Member States in building capacity and exchanging experiences with regard to transparency, participation and accountability in fiscal policies.

As indicated in the Introduction, the High-Level Principles were intended to promote increased convergence and coherence across the large number of international fiscal transparency instruments. They were also intended to help identify gaps in standards and norms, and to promote the development of new or enhanced instruments as necessary.

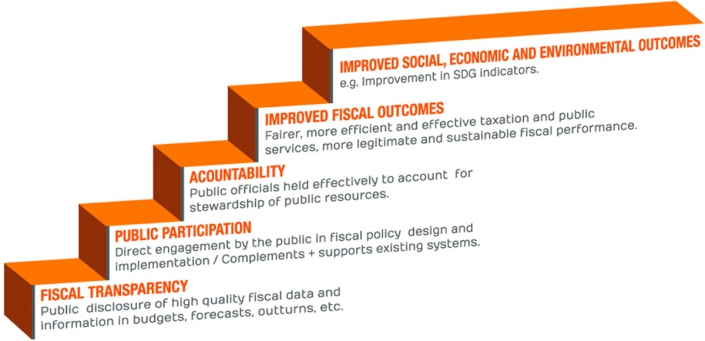

To that extent the High-Level Principles were viewed as sitting at the top of a hierarchy of principles, standards and norms (the second level) and assessments of country practices (the third level) – as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Hierarchy of Fiscal Transparency Principles, Standards and Assessments

An illustration of how the High-Level Principles have impacted on standards and norms is through considering High-Level Principle 10 on public participation. As noted in the Introduction, a right to direct public participation in fiscal policy design and implementation had not previously been asserted in an international fiscal transparency instrument. There was a lack of guidance on what the principle meant in practice, although the International Budget Partnership led the way when it introduced a section on public participation practices in the 2012 Open Budget Survey.

In 2012 GIFT therefore embarked on a multi-year work program to generate greater knowledge about country practices and innovations in citizen engagement. Outputs produced include country case studies, a set of GIFT Principles of Public Participation in Fiscal Policy, a Guide on Public Participation in Fiscal Policy, and instruments to measure public participation in fiscal policy (see the discussion under High-Level Principle 10 for further details).

Since 2012, elements of public participation have been incorporated in the leading international fiscal transparency instruments: by the IMF, the OECD, the Open Budget Survey (Section 5 of which was redesigned in 2017 to measure performance against the GIFT Participation Principles), the Public Expenditure and Accountability initiative (PEFA), and the new Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool (TADAT).

More generally, since 2012 the GIFT coordination team has reviewed the consultation drafts of the revised and new fiscal transparency standards as they were being developed, against the High-Level Principles. The objective has been to promote greater coherence across all the instruments, and to achieve a better reflection of the High-Level Principles e.g. with respect to public participation but also in other respects. Examples include GIFT comments on the draft IMF Fiscal Transparency Code, (including the separate draft of Pillar IV of the Code on Resource Revenue Transparency), on the draft OECD Principles of Budgetary Governance, on the draft participation section of the Open Budget Survey, and on the draft of the revised PEFA.

The independent evaluation of GIFT in 2016 undertook a detailed analysis of the influence of GIFT and the High-Level Principles on the revisions to the main fiscal transparency standards and instruments that took place in the period 2013-2016. The evaluation concluded that ‘GIFT has been highly successful in its work to harmonize norms and standards regarding fiscal transparency and public participation.’[7]

GIFT has also mapped the fiscal transparency commitments made by members of the Open Government Partnership to help identify patterns, promising areas of reform, and areas that might be given more emphasis, and to compare implementation progress across countries. The GIFT coordination team has used the High-Level Principles when reviewing draft OGP National Action Plans and in providing suggestions on how the draft Plans could be strengthened or on commitments to consider for future plans.

Looking ahead, GIFT Stewards have used the High-Level Principles to frame their thinking in formulating the 2018-2021 GIFT Strategic Plan. In this period GIFT will focus on placing the citizen at the centre of fiscal transparency efforts. This will involve supporting citizen efforts to monitor how their taxes are collected and how public money is being spent, and to have a say in the design and implementation of tax and spending policies.

A specific goal is to better link budget information with areas that more directly affect people’s lives. The challenge is that current global standards and norms fall short on encouraging and guiding the publication of detailed and meaningful spending information that public service users and local communities need. In public service delivery, one of the missing links between transparency and participation is granularity: the disclosure of facility-level and transaction-level information. Currently, there is no international norm on the level of detail required for routine disaggregated reporting on the administrative classification of budget information that would make it possible for citizens to see how individual service delivery units – such as schools or health centers – allocate and spend their budgets. We are also talking here about better disclosure practices in terms of reusable data formats, improved quality of online portals/websites, and the ability to cross-reference different types of data.

These activities will help to strengthen implementation of High-Level Principles 3 (publication of high quality fiscal data), 4 (transparency of outputs and of resources entrusted to governments), and 10 (public participation).

In the future, GIFT will address these gaps in an effort to promote budgets, fiscal reports and other documents that are more understandable, readable and detailed. Routine disclosure of the budgets of individual service delivery units could also support much more direct engagement between service users and local communities, on one hand, and the managers of service delivery units. Research to better understand the gap between the information supplied and the users’ needs will be part of this effort. Framed under these considerations, GIFT will continue the work on the disclosure of useful information for citizens, such as procurement, and public service delivery data, following examples and models on granularity that GIFT government stewards and partners are required to report on their budgets at the national level.

Similarly, more attention will be paid to direct public engagement over the design and implementation of revenue policies. From its inception, GIFT has defined fiscal transparency as a broader concept than budget transparency. On the revenue side, this basically refers to the right to participate in debates over revenue policies and address publicly and informatively the degree to which tax burdens are progressive and fair.

GIFT will facilitate a conversation between the increasing number of stewards and partners that have been working on tax policies and tax administration issues from different perspectives, in a dialogue that could help identify gaps and complementarities between the different approaches, emphasizing access to information concerning government revenues and direct public engagement, in order to conduct relevant analysis, and addressing the question of inequality.

In sum, the GIFT network will be focusing in the areas that will frame the debate and lead the reforms on transparency in the future: the disclosure of quality fiscal information in formats and ways that are meaningful to the users; the right to public participation in fiscal policies, particularly the design and delivery of public services; and public engagement in the processes through which tax and budget policies reflect public priorities and solve the problems that matter to people.

[1] “Understanding of governments’ underlying fiscal position and the risks to that position remains inadequate. This was demonstrated by the emergence of previously unreported fiscal deficits and debts and the crystallization of large, mainly implicit, government liabilities to the financial sector during the current crisis…A revitalized fiscal transparency effort is needed to address the shortcomings in standards and practices revealed by the crisis and guard against a resurgence of fiscal opacity in the face of growing pressures on government finances’ ‘Fiscal Transparency, Accountability, and Risk’, IMF, August 7, 2012.

[2] Open Budget Survey 2012, http://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/OBI2012-Report-English.pdf

[3] GIFTs founding Lead Stewards were the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the International Budget Partnership, the Federal Secretary of Budget and Planning of Brazil and the Department of Budget and Management of the Philippines. The International Federation of Accountants, and the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit of Mexico, have since been admitted as Lead Stewards. There is a wider group of Stewards, numbering 37 as at January 2018, including 13 budget-related government institutions, 12 national or regional CSOs, 5 international CSOs, 3 multilateral organisations, 3 private foundations, and 1 international development institution. See https://fiscaltransparency.net/about/

[4] Defining the Technical Content of Global Norms: Synthesis and Analytic Review: Phase I and Phase II Reports, December 2011. Available at www.fiscaltransparency.net

[5] The Principles, together with the accompanying preamble, are reproduced in Annex 1. They are also available at https://fiscaltransparency.net/ft_principles/#toggle-id-1

[6] The Resolution is also available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/67/218

[7] Swedish Development Advisers (2016), Independent Evaluation of the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (2013-2016).’ Gothenburg, November 29.

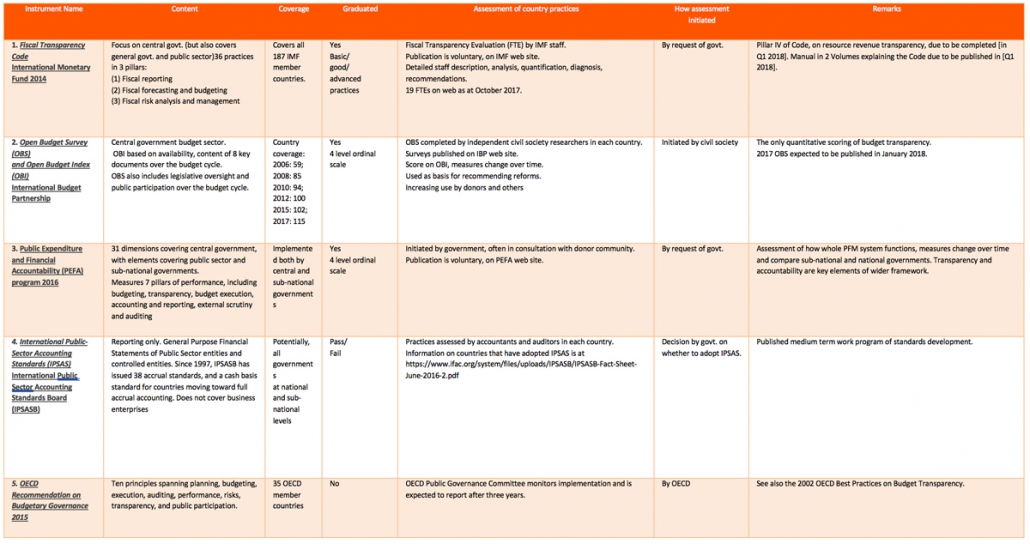

Figure 3 presents a stylized mapping of international fiscal transparency instruments. The aim is to provide a quick overview of all the current instruments and their key features, as well as to provide direct access to the individual web sites for further information.

Figure 3 is organized in three categories according to whether instruments provide for:

- Disclosure of fiscal information

- Public participation in fiscal policy, or

- Oversight of fiscal policy.

- These three domains relate to the three key parameters for GIFT as expressed in the High-Level Principles: transparency, participation, and accountability.

Sub-categories of the three domains provide additional information about the nature of instruments, while the zones of intersection between the three domains show instruments that cover two of the three domains, or all three domains.

Figure 3: Mapping current international fiscal transparency instruments

Download the PDF for a better visualization

Table 1 narrows down the focus considerably to provide a summary of key elements of just the core international fiscal transparency instruments.

The aim of Table 1 is to assist those in government or other public institutions, or in civil society or international organisations, to decide which of the core standards and assessment instruments might be most appropriate to their circumstances, how to initiate activity, and what the scope and other features of these instruments are.

Table 1: Key elements of the core international fiscal transparency instruments

IV. Guide to the individual GIFT High-Level Principles

Access to Fiscal Information

High-Level Principle One

Everyone has the right to seek, receive and impart information on fiscal policies. To help guarantee this right, national legal systems should establish a clear presumption in favour of the public availability of fiscal information without discrimination. Exceptions should be limited in nature, clearly set out in the legal framework, and subject to effective challenge through low-cost, independent and timely review mechanisms.

Why this is important

Access to information is a precondition for the public to be able to take informed decisions regarding basic needs, safety, access to public services and other crucial factors related to wellbeing. It is also crucial for citizens to be able to access information about the public affairs that concern them, and for the public to hold officials and the government as a whole to account for fiscal management. In addition, access to information is a precondition for meaningful public participation in fiscal policy. The right to fiscal information is an important guarantor of the ability of the public to obtain information in practice.

The right to government information is enshrined in laws in over 110 countries. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that government-produced information belongs to the general public and must be accessible by anyone who requests it, unless it needs to be classified for reasons of public interest (national security, ongoing investigations processes, privacy, etc.), and there is a legal basis for this classification.

There are limits to the right to fiscal information. The most significant ones are related to the privacy of individuals. If transparency is important for democracy, protection of privacy is crucial for individual liberty and the freedom of thought. The balance between transparency and privacy protection is a complicated matter. In most countries, it is a result of a public debate and a legislative definition that establishes the tradeoff between privacy and publicity on the use of public resources. For instance, the economic compensation of public servants can be public information, but how much such individuals pay in taxes may be protected by confidentiality (although in one or two countries this also is public e.g. Sweden). In another example, while the names of beneficiaries of direct cash transfers are disclosed in Mexico and Brazil, the beneficiaries of similar subsidies have their names concealed in Spain or Germany. In one place, the public interest favors the disclosure of the names of all public resource beneficiaries, while personal data protection prevails as the value that must be protected in other places. In any case, it is important that these limits are clearly set out in the legal framework, to avoid as much as possible discretion in the interpretation and enforcement of the law.

The origins of the right to information principle

The right of citizens to fiscal information is at least as old as the French declaration of the rights of man and citizen, 1789, which stated: ‘All citizens have the right to ascertain, personally or through their representatives, the necessity of the public tax, to consent to it freely, to know how it is spent, and to determine its amount, basis, mode of collection, and duration.’ (Article 14).[1]

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) states that everyone has the right to freedom of expression, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds. This includes all individuals within a state and subject to its jurisdiction, not just citizens. Similar language appears in Article 17 of the African (Banju) Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and in other regional conventions, such as Article 13 of the American Convention. The Human Rights Committee, which interprets the ICCPR, in September 2011 clarified that the Convention establishes a right to public access to information held by public agencies.

Article 19 applies to all branches of the State (executive, legislative and judicial) and other public or governmental authorities, at whatever level – national, regional or local. Such responsibility may also be incurred by a State party under some circumstances in respect of acts of semi-State entities.[2]

Article 19 states that this right may be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: (a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) For the protection of national security or of public order, or of public health or morals.

The ICCPR has been in force since 1976, and as of October 2011 had 74 signatories and 167 parties. It has the force of international treaty law.

The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992, in Principle 10, states that, at the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities…States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.

The UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (the Aarhus Convention) sets out a rights-based approach to access to environmental information, public participation, and binding independent review of decisions on access to environmental information and decisions.

The Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Universal Declaration on Democracy (1997) stipulates that accountability entails a public right of access to information about the activities of government, the right to petition government and to seek redress through impartial administrative and judicial mechanisms.

One of the Open Government Partnership’s eligibility criteria is the right to access to information, as it requires member countries to have a law on access to information law, right to information as a constitutional provision, or a draft initiative under consideration. On access to fiscal information, the OGP requirements also demand the timely publication of essential budget documents, such as the budget proposal and the audit report.

The members of the Organization of American States declared in 2009 that “access to information held by the State, subject to constitutional and legal norms, including those on privacy and confidentiality, is an indispensable condition for citizen participation and promotes effective respect for human rights.” After that, the OAS member States, agreed on a preparation of a Model Inter-American Law on Access to Information to provide States with the legal foundation necessary to guarantee the right to access to information, as well as an Implementation Guide for the Model Law to provide the roadmap necessary to ensure the Law functions in practice (http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/access_to_information_model_law.asp). In June 2010, the OAS General Assembly adopted resolution AG/RES 2607 (XL-O/10) (http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/docs/AG-RES_2514-2009_eng.pdf) on the Model Law. The Model Inter-American Law and the Guide for its Implementation, incorporate the principles outlined by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights in Claude Reyes v. Chile, as well as the Principles on Access to Information adopted by the Inter-American Juridical Committee. [CJI/RES. 147 (LXXIII-O/08)]. Similarly, the African Union approved a model law for Africa in 2012 (http://www.achpr.org/instruments/access-information).

One important characteristic of these more recent model laws is that they take into consideration the era of internet and new technologies, with the possibility to disclose significant amounts on government information on line. These legislative pieces support the proactive disclosure of government information that is supposed to be very useful for citizens or frequently requested. Among the key classes of information subject to proactive disclosure by a public authority is the description of its organizational structure, functions, duties, locations of its departments and agencies, operating hours, and names its officials; the qualifications and salaries of senior officials; the internal and external oversight, reporting and monitoring mechanisms relevant to the public authority including its strategic plans, corporate governance codes and key performance indicators, including any audit reports; and its budget and its expenditure plans for the current fiscal year, and past years, and any annual reports on the manner in which the budget is executed.

This important feature of access to information laws is less common in legislations approved before the year 2000.

A right to fiscal information is also suggested by the reciprocal relationship between citizens and government, in which citizens provide resources to and entrust governments with stewardship over public resources, and, in turn, expect to have access to fiscal information.

How is this Principle reflected in existing international norms and standards?

General freedom of information laws apply in over 111 countries (see the Global Right to Information Rating, by the Centre for Law and Democracy). However, a right to fiscal information has not previously been included in an international instrument on fiscal transparency.

There are two ways to access government information: governments can proactively disclose it, or they can provide access in response to an official information request. A key aspect of the right to information is the rules on the proactive disclosure of information. Fiscal transparency holds a central role in access to information legal regulations, for two reasons: the public nature of budget resources, originated in the taxes paid by the people, and the fact that the sections on proactive disclosure of these laws usually devote special attention to the obligation to publish information about the budget and fiscal resources, without the need of having requests for such information.

That said, although fiscal transparency is a central part of proactive disclosure provisions in many countries, disclosure rules are often spread among many different pieces of legislation, such as procurement laws, public investment, public works and infrastructure regulations, decentralization provisions and budget responsibility laws, which frequently include specific stipulations on proactive disclose of fiscal activities and public funds.

The right of access to fiscal information is strongly present in the 2015 restructured version of the International Monetary Fund Fiscal Transparency Code. The Code is composed of 36 principles in total and 17 of them are related to proactive fiscal transparency proactive disclosure. In all pillars of the FT-Code, various principles indicate that information should be proactively disclosed to the public: six principles related to fiscal reporting (tax expenditures, in-year fiscal reports, financial statements, revisions to historical statistics, fiscal statistics and annual financial statements) , four principles on the fiscal forecasting and budgeting chapter (financial obligations under investments projects, budget documents, objectives and results, implications of budget policies), and seven principles of the fiscal risks’ analysis forecasting and management pillar (main specific risks, guarantee exposure, obligations under public-private-partnerships, fiscal exposure of the financial sector, exploitation of natural resources, exposure to natural disasters, financial condition of subnational governments).

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development published in 2002 the Best Practices for Budget Transparency, which define budget transparency as “the full disclosure of all relevant fiscal information in a timely and systematic manner”, and outlines “specific disclosures”, that is various types of information (such as economic assumptions, financial assets and liabilities, and contingent liabilities) which should be included in budget reports. In 2015, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance set out ten Budget Principles, presenting an overview of how various aspects of budgeting should inter-connect to form a coherent and effective system. The Principles supplement many elements of the Best Practices, including the principle of transparency, openness and accessibility and by introducing a principle of participative and inclusive budgetary debate.

Finally, the OECD published in 2017 the Budget Transparency Toolkit, which include a section devoted to providing useful budget related documents during the annual cycle and including the right financial information in budget related documents. On publication of budget documents, the OECD recommends that official documents should provide a useful overview of the fiscal activities of the public sector in a regular and timely manner, to inform better scrutiny and decision-making throughout the budget cycle.

The new PEFA framework of 2016 clearly addresses in many of its indicators the questions of public access to public finance information and, in a some of them, the issue of the quality of information. PEFA emphasizes transparency and accountability in terms of access to information, reporting and audit, and dialogue on PFM policies and actions. In 14 of the 31 indicators, the question of the publication of Public Financial Management documents is introduced and consistently, the transparency question is related to better practices. This means that the new PEFA framework provides a very valuable source of information related to fiscal transparency. Pillar 2 on transparency of public finances, Pillar 3 on management of assets and liabilities, Pillar 4 on policy-based fiscal strategy and budgeting, Pillar 6 on accounting and reporting and Pillar 7 on external scrutiny and audit, all include the importance of pro-actively disclosed information in some of their dimensions.

In sum, the new IMF-Code, PEFA assessment and the OECD toolkit provide a valuable analysis of the fiscal transparency of PFM systems.

The International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Survey (OBS) 2015 is completely about the right to fiscal information: this is a comprehensive analysis and survey that evaluates whether governments give the public access to budget information and opportunities to participate in the budget process at the national level. The IBP works with civil society partners in 102 countries to collect the data for the Survey. The first Open Budget Survey was released in 2006 and will be conducted biennially. The OBS edition 2015 asks whether citizens have the right in law to access government information including budget information. General question 3 addresses specifically this point. The focus on public access to information, as well as opportunities to participate in budget processes, is what makes the questionnaire unique among assessments of government transparency and accountability.

The Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Parliament And Democracy In The Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Good Practice stipulates that the legislature should operate transparently, including proceedings being open to the public; prior public information on the business before parliament; documentation available in relevant languages; availability of user-friendly tools; and legislation on freedom of/access to information.

Country Practices

An index of the quality of the legal environment for general Freedom of Information laws in 111 countries, based on 61 indicators, is available at http://www.rti-rating.org/country-data/ The 61 indicators are in seven categories: right of access; scope; requesting procedures; exceptions and refusals; appeals; sanctions and protections; and promotional measures. The findings show a significant variation in the quality of the legal framework, with scores ranging from 33 (Austria) to 136 (Mexico) out of a maximum of 150. More recent laws protect the right to know more strongly; of the 20 countries with scores above 100, twelve adopted their laws since 2005.

A growing number of countries have established an Ombudsman/Office of Public Protector/Information Commissioner with authority to investigate individual public complaints about denial of access to official information. Sweden is the country with the longest tradition of an independent Ombudsman.

Access Information Europe and the Centre for Law and Democracy, in collaboration with the International Budget Partnership, coordinated an initiative in 2010-11 to monitor the right of access to budget information in practice – the Ask Your Government! 6 Question Campaign. A network of civil society organisations submitted 480 requests for budget information in 80 countries. In response to over half of the requests, no information at all was provided – in spite of the fact that requesters made multiple resubmissions of the questions and made other efforts to elicit a response. Only 12 countries complied with Right To Information standards.

An IBP Research Note investigated the prevalence of legislation requiring fiscal transparency, and public participation in the budget process. [3] About half of the 125 countries surveyed incorporated some mention of budget transparency in their laws. 14 countries provide very extensive coverage of budget transparency matters in their legislation. However, the inclusion of detailed transparency clauses in budget laws does not necessarily result in better practice; just as the lack of such laws or provisions does not inhibit good practice.

The Open Budget Survey 2015[4] found:

- In 89 out of 102 countries do citizens have the right in law, and generally in practice, to access government information including budget information. The most common rating was ‘d’ (30 countries) where either the right to information including budget information is not codified, or it is frequently or always impossible in practice to obtain access.

Sources of further technical guidance

The GIFT Phase 2 Report for the Advancing Global Norms Working Group, Defining the Technical Content of Global Norms: Towards a New Global Architecture, 2 December 2011 (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2), contains a summary of Official International Instruments, and Civil Society International Instruments that contain provisions on citizens’ right to information: https://fiscaltransparency.net/

The UN Human Rights Committee has published an explanatory note on Article 19:

Human Rights Committee, 102nd session, Geneva, 11-29 July 2011. General comment No. 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression.

The Inter-Parliamentary Union’s Parliament And Democracy In The Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Good Practice (Chapter 3): http://www.ipu.org/dem-e/guide.htm

The IMF Fiscal Transparency Manual 2007 (pp. 85-90) on commitment to the publication of fiscal information: http://www.imf.org/external/ns/search.aspx?NewQuery=fiscal+transparency+manual&col=&submit.x=0&submit.y=0

The IMF’s Special Data Dissemination Standard: http://dsbb.imf.org/Pages/SDDS/Overview.aspx

Transparency and Participation in Public Financial Management: What Do Budget Laws Say? Paolo de Renzio, International Budget Partnership, Verena Kroth, London School of Economics. IBP research Note Number 1, September 2011.

[1] See Irwin, T, 2013, Shining a Light on the Mysteries of State: The Origins of Fiscal Transparency in Western Europe, IMF Working Paper WP/13/219.

[2] Human Rights Committee, 102nd session, Geneva, 11-29 July 2011. General comment No. 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, paragraph 7.

[3] de Renzio and Kroth, 2011.

[4] Results from the 2017 OBS were not available at time of completion of this Guide.

High-Level Principle Two

Governments should publish clear and measurable objectives for aggregate fiscal policy, regularly report progress against them, and explain deviations from plans.

Why this is important

A fundamental premise of good management in any part of the public or private sector is the need for those in authority to state clearly and openly to their stakeholders the intended overall outputs and impacts of their policies, as well as the resources they will consume, and to report on aggregate progress and results. Because aggregate fiscal policy has substantial effects on the national economy immediately, and in the future, including on employment, inflation, growth, resource allocation and debt, it is important that governments are clearly accountable for the impacts of fiscal policy on national welfare.

What is aggregate fiscal policy?

Aggregate fiscal policy is the level of fiscal policy that influences the economy at large. Its main dimensions are overall government revenues and spending, the fiscal deficit, and public debt. the allocation of resources to sectors and policy priorities is level 2, and the delivery of public services is level 3 (see for instance the desirable fiscal and budgetary outcomes ofPEFA 2016 Framework (1.2)).

How is this Principle reflected in existing international norms and standards?

The IMF Fiscal Transparency Code (‘the Code’) stipulates that the government should ‘state and report on clear and measurable objectives for the public finances’ (principle 2.3.1). This requires the specification of a ‘numerical objective for the main fiscal aggregates’, which should ideally be precise, time-bound, and stable. The Code further specifies that ‘budget documentation and any subsequent updates explain any material changes to the government’s previous fiscal forecasts, distinguishing the fiscal impact of new policy measures from the baseline’ (principle 2.4.3). The Code also stipulates that basic practice on the medium-term budget framework requires budget documentation to include ‘medium-term projections of aggregate revenues, expenditures, and financing….’ (principle 2.1.3).

Under fiscal risk analysis, the Code prescribes that the government ‘regularly publishes projections of the evolution of the public finances over the long-term’ (principle 3.1.3) and ’provides a summary report on the main specific risks to its fiscal forecasts’ (principle 3.1.2). The draft Pillar IV[1] of the Code reinforces the supremacy of aggregate fiscal policy objectives by stipulating that resource revenues should be ‘managed through the annual budget in accordance with predefined fiscal policy objectives’ (principle 4.4.1).

The OECD Principles of Good Budgetary Governance recommend that governments commit to ‘pursue a sound and sustainable fiscal policy’ (principle 1b) and consider whether ‘the credibility of such a commitment can be enhanced through clear and verifiable fiscal rules or policy objectives….’(principle 1c). Under the OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency, the pre-budget report should ‘explicitly state the government’s long-term economic and fiscal policy objectives and the government’s economic and fiscal policy intentions for the forthcoming budget and, at least, the following two fiscal years’ (section 1.2). The OECD Principles of Good Budgetary Governance also call for governments to closely align budgets with medium-term strategic priorities by ‘developing a stronger medium-term dimension in the budgeting process….’ (principle 2a).

The Open Budget Survey (OBS 2015) [2] asked whether the Executive’s Budget Proposal or any supporting budget documentation presented information on ‘how the proposed budget (both new proposals and existing policies) was linked to government’s policy goals’ for the budget year and for a multi-year period (Questions 47 and 48).

PEFA Indicator PI-15.2 assesses the extent to which ‘government prepares a fiscal strategy that sets out fiscal objectives for at least the budget year and the two following fiscal years’. It identifies a well-formulated fiscal strategy as one that ‘includes numerical objectives, targets or policy parameters (such as the level of fiscal balance), aggregate central government expenditures or revenues, and changes in the stock of financial assets and liabilities’. PEFA Indicator PI-15.3 assesses the extent to which the ‘government makes available—as part of the annual budget documentation submitted to the legislature—an assessment of its achievements against its stated fiscal objectives and targets’. The assessment ‘should also include an explanation of any deviations from the approved objectives and targets as well as proposed corrective actions’.

Country Practices

The Open Budget Survey 2015 (Questions 47 and 48) found that:

- 44 countries out of 102 published estimates in their executive’s budget proposal (with or without a narrative discussion) showing how the proposed budget was linked to all the government’s policy goals for the budget year; and

- 26 countries published such estimates for a multi-year period.

Examples of countries with legally binding fiscal rules include:

- In Austria, an amendment to the federal budget law stipulates that the structural deficit at the federal level (including social insurance) shall not exceed 0.35 percent of GDP.

- In Chile, a structural balance rule in place since 2001 requires government expenditures to be budgeted ex ante in line with structural revenues. Small changes have been made over time to the target structural balance, or its path, and a de facto escape clause accommodates counter-cyclical measures.

- In Norway, the budget balance rule, adopted in 2001, requires the non-oil structural deficit of the central government to equal the long-run real return of the Government Pension Fund (assumed to be 4 percent). Temporary deviations are allowed over the business cycle and in the event of extraordinary changes in the value of the Government Pension Fund.

- In New Zealand, the Fiscal Responsibility Act sets out the principles for responsible fiscal management, including rules for the budget and debt. While not itself specifying quantitative rules, the Act requires the government to set out specific fiscal targets for 3-year and 10-year objectives, typically in percent of GDP.

In the European Union, national fiscal policies are guided by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which is a fiscal rule-based framework. The SGP commits EU governments to country-specific budgetary targets, known as medium-term budgetary objectives.

The OECD International Budget Practices and Procedures Database contains detailed information about fiscal rules, medium-term expenditure targets, and other fiscal objectives in responding countries. The 2007/08 Database covers 97 countries, including 31 OECD members; the 2012 Database covers 34 OECD countries.

Sources of further technical guidance

The OECD Budget Transparency Toolkit 2017 contains topics on the content of a pre-budget statement and the main budget relating to the government’s fiscal strategies, as well as a long-term report and reporting on fiscal risks (section A). It also contains citations of relevant international standards, selected country examples of good practice, and sources of further guidance http://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/budget-transparency-toolkit.htm

IMF Fiscal Transparency Code https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/consult/2016/ftc/pdf/050916.pdf

Open Budget Survey 2015: http://internationalbudget.org/what-we-do/open-budget-survey/

Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA): Framework and Assessment Fieldguide: https://pefa.org/

IMF Fiscal Transparency Manual 2007 (pp. 37-43) on medium term budget frameworks and fiscal rules: http://www.imf.org/external/ns/search.aspx?NewQuery=fiscal+transparency+manual&col=&submit.x=0&submit.y=0

IMF Guide on Resource Revenue Transparency 2007 (pp. 29-31 and Box 3): http://www.imf.org/external/np/fad/trans/guide.htm

OECD Budget Practices and Procedures Survey https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/internationalbudgetpracticesandproceduresdatabase.htm; http://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=7F309CE7-61D3-4423-A9E3-3F39424B8BCA

European Union: Stability and Growth Pact http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/economic_governance/sgp/index_en.htm

Andrea Schaechter, Tidiane Kinda, Nina Budina, and Anke Weber, 2012, Fiscal Rules in Response to the Crisis—Toward the “Next-Generation” Rules. A New Dataset. IMF Working Paper 12/187 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12187.pdf

[1] The draft IMF Natural Resource Fiscal Transparency Code (May 9, 2016) can be accessed at:

https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/consult/2016/ftc/pdf/050916.pdf

[2] Results from the 2017 OBS were not available at time of completion of this Guide.

High-Level Principle Three

The public should be presented with high quality financial and non-financial information on past, present, and forecast fiscal activities, performance, fiscal risks, and public assets and liabilities. The presentation of fiscal information in budgets, fiscal reports, financial statements, and national accounts should be an obligation of government, meet internationally-recognized standards, and should be consistent across the different types of reports or include an explanation and reconciliation of differences. Assurances are required of the integrity of fiscal data and information.

Why this is important

The core of fiscal transparency is publication of high quality fiscal information. It is a precondition for legislative oversight, and for the public to understand and participate in the budgetary process, judge the government’s performance, and hold it to account. Essential attributes of high quality information include the need for data to be comprehensive, regular, timely, reliable, useful, easily understood, readily accessible, and subject to standards that are internationally accepted.

What is the difference between budgets, fiscal reports, financial statements, and National Accounts?

Budgets are forward-looking. They are statements of how a government proposes to raise revenues, spend resources, and finance its operations in the coming year in order to advance towards specified outputs and results. Budgets usually focus on cash transactions, but a handful of countries now implement accrual budgeting (Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Iceland, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). Government budgets are incorporated in legal instruments that authorize taxation and government spending.

Fiscal reports are records of a government’s actual (historical) revenues, spending and financing. They may report the fiscal activities of the central government, state governments, or local governments, or of all levels of government in a country (referred to as the general government). Reports may cover a whole government in aggregate as an entity, and/or individual government entities e.g. ministries, departments or agencies. They may record within-year activities e.g. monthly or quarterly reports, or previous year(s) outturns. They may be on a cash or accruals basis (full or partial).

Financial Statements are reports compiled from accounting data after the end of a period, which is usually a year but may be more frequent. They may be cash or accrual or some variant thereof, and may cover the whole government or an individual government entity. Annual financial statements are usually incorporated or included as separate documents in the government’s year-end reports (which also usually include material on differences from budget estimates and reports on non-financial performance). Accrual financial statements include a statement of financial performance, a statement of financial position (balance sheet), and a statement of cash flows.

National accounts measure the economic activity of a nation, including the contributions of individual economic sectors (households, corporations, government) to national output, expenditure, and income. Statistics on the government sector are referred to as government finance statistics (or fiscal statistics). They are derived from accounting data and statistical series, and facilitate analysis of the impact of government on the rest of the economy for the purpose of macroeconomic analysis and decision making. About one-third of countries report fiscal statistics on a partial or full accruals basis.

What are assurances of integrity of fiscal data?

Mechanisms, both internal to the executive, and independent of the executive, can help to ensure that fiscal data and information are reliable and maintain quality standards. Internal mechanisms include appropriately applied accounting standards; an effective control and audit environment; systematic data reconciliation processes; and technically sound and objective macroeconomic and fiscal forecasting procedures. Independent mechanisms include effective auditing by the Supreme Audit Institution, procedures for exposing macroeconomic and fiscal data and forecasts to external expert scrutiny, such as by an Independent Fiscal Institution; technical independence of the national statistics agency; and independent data verification processes such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

How is this Principle reflected in existing international norms and standards?

International codes and standards place the availability of high-quality information at the core of good fiscal transparency practice and provide strong guidance on the required coverage and quality of fiscal data. They also recommend that the provision of budgetary information be grounded in law.

The IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual (GFSM 2014) provides some of the core standards that are widely adopted across the main fiscal transparency instruments. These include the classification of the government sector and the public sector (based on the UN SNA), the classification of the levels of government, and the economic and functional classification of expenditures (the latter based on the UN Classification of the Functions of Government, COFOG). GFSM 2014 also contains a classification of revenues.

The IMF Fiscal Transparency Code (‘the Code’) opens with a rigorous set of requirements for fiscal reporting (Pillar 1), supplemented by further detail in Pillars II and III. Principle 2.2.1 also requires that the legal framework clearly defines ‘key contents of the budget documentation’. The draft Pillar IV[1] focuses on the greater specificity required for natural resource activities. Specifically, the Code recommends that:

The scope of fiscal reports should:

- ‘cover all entities engaged in public activity, according to international standards’ (principle 1.1.1);

- ‘cover all public revenues, expenditures, and financing’ (principle 1.1.3)

- ‘include a balance sheet of public assets, liabilities, and net worth’ (principle 1.1.2)

- ‘be published in a frequent, regular, and timely manner’ (principle1.2).

- (value) ‘the government’s interest in exhaustible natural resource assets and their exploitation……’ (principle 3.2.6).

Fiscal reports should include the following information:

- ‘revenues, expenditures, and financing of all central government entities …. on a gross basis in budget documentation’ (principle 2.1.1);

- ‘outturns and projections of revenues, expenditures, and financing over the medium term on the same basis as the annual budget’ (principle 2.1.3);

- ‘projections of the evolution of the public finances over the long-term’ (principle 3.1.3);

- ‘how fiscal outcomes might differ from baseline forecasts as a result of different macroeconomic assumptions. (principle 3.1.1);

- ‘regular summary reports on the main specific risks to [the government’s] fiscal forecasts’ (principle 3.1.2); and

- for resource-rich economies, ‘regular reporting on resource revenue collection activities, audit and compliance activities’ (draft principle 4.2.3).

Quality and integrity require that:

- ‘Fiscal statistics are compiled and disseminated in accordance with international standards’ (principle 1.4.1).

- ‘Fiscal forecasts, budgets, and fiscal reports are presented on a comparable basis, with any deviations explained’ (principle 1.4.3).

- ‘Information in fiscal reports should be relevant, internationally comparable, and internally and historically consistent’ (principle 1.3);

- ‘Annual financial statements are subject to a published audit by an independent supreme audit institution, which validates their reliability’ (principle 1.4.2).

- ‘Economic and fiscal projections and performance are subject to independent evaluation’ (principle 2.4.1).

- For resource-rich economies, ‘government reports on resource revenue collection are reconciled with company reports on fiscal payments’ (draft principle 4.2.4)

For resource-rich economies, the Code recommends, in addition, that:

- ‘There is an open process for the allocation of resource rights’ and ‘the government maintains and publishes an up-to-date register of all resource rights holdings, with details of their beneficial owners’ (draft principles 4.2.1 and 4.2.2).

- ‘All resource companies regularly disclose payment information on their domestic natural resource exploration, extraction and trading activities’ (principle 4.3.1).

The OECD Principles of Good Budgetary Governance call for budget documents and data to be ‘open, transparent and accessible’ (principle 4). Budget reports should be clear and factual (principle 4a) and published ‘fully, promptly and routinely’ (principle 4c). All expenditures and revenues of the national government should be accounted comprehensively and correctly in the budget document (Principle 6a) and a full national overview of the public finances, including sub-national levels of government, should be presented (principle 6b).

The OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency sets out detailed requirements for the publication of data and other information in the government’s budget, pre-budget report, monthly reports, mid-year report, year-end report, long term report and a pre-election report. It notes that ‘a summary of relevant accounting policies should accompany all reports’, including disclosure of ‘any deviations from generally accepted accounting practices’, and ‘the same accounting policies should be used for all fiscal reports’. The Best Practices also include provisions designed to provide assurance of data integrity, and requirements for information on assets, liabilities, and contingent liabilities.

The OECD Practical Toolkit on Budget Transparency 2017 contains a section H on making budget information accessible to the public. This includes topic H.1; Presenting key budget information in a clear manner that can be understood easily by the public and by civil-society stakeholders; and H.2, publishing a Citizen’s Budget. Section I, using open data to support budget transparency, contains topics I.1 Open data should meet minimum standards; I.2 on requirements for access to open budget data; and I.3 on integrating open budget data portals with existing portals.

International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) apply to the financial statements of national and sub-national governments, and other public sector bodies, apart from government business entities. To date, there are 38 accrual standards, which contain, where appropriate, transitional provisions for entities to attain full compliance. IPSAS 24 requires a comparison of budget and actual to be included in the financial statements of entities that are required to or elect to publish their budgets. The International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) Study 14, Transition to the Accrual Basis of Accounting: Guidance for Governments and Government Entities provides further assistance. IPSASB has also issued a cash basis IPSAS standard for governments.

The Open Budget Survey, published every two years, contains around 100 detailed questions on the past, current and forecast fiscal information included in the budget documents, and on fiscal reporting during and at the end of the year. These questions provide a thorough guide to the scope and content of information that might be disclosed by national governments under this high-level principle. For example, in the Open Budget Survey 2015[2]:

- Questions 1-46 on the Executive’s Budget Proposals and questions 54-58 on the Pre-Budget Statement explore the depth and breadth of information supplied on past and proposed government spending, revenue, borrowing, debt, and assets; and the underlying macro-economic forecast.

- Questions 59-63 on the Enacted Budget focus on the detail provided on spending and revenue estimates and implied borrowing.

- Questions 85-86 and 88-89 on the End-Year Report ask about the detail provided on spending and revenue outcomes.

A range of PEFA indicators assess the provision of fiscal information:

- PI-5 measures the extent to which annual budget documentation incorporates twelve specified elements of information (among which four are considered basic and critical), including a forecast of the fiscal deficit or surplus, aggregated revenue and expenditure data for the current and previous year, debt stock, financial assets, and aspects of fiscal risk.

- PI-14 records the inclusion of forecasts of key fiscal and macroeconomic indicators in budget documentation and some sensitivity analysis.

- PI- 16.1 measures the detail to which expenditure estimates are recorded in the annual budget.

- PI-28 and PI-29 measure dimensions of in-year reports on budget execution, and the annual financial report.

Several PEFA indicators specifically target the provision of fiscal information to the public:

- PEFA indicator PI-8 covers access to information on public service delivery, including budget resources that reached service delivery units as planned.

- PI-9 measures the ready availability to the public of major reports including the annual executive budget proposal documentation as presented under PI-5, execution reports, audited annual financial statement, citizens’ budget, and macroeconomic forecasts.

- PI-10 measures the extent to which fiscal risks to central government from public corporations, sub-national governments, and contingent liabilities are published.

- The publication of information on implementation of major investment projects is covered by PI-11.4.

- PI-12 highlights whether information on assets is made available to the public.

Other PEFA indicators assess the integrity of fiscal data, such as internal controls; accounts reconciliations; and internal audit; adequacy and comparability.

The IMF’s Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS) sets good practices (‘monitorable dimensions’) for data publication in terms of coverage, periodicity, and timeliness; ease of access; integrity; and quality. The SDDS was established for governments that have, or might seek, access to international capital markets. Most countries not subscribing to the SDDS participate in the General Data Dissemination System enhanced (GDDS), or enhanced GDDS, which also guide provision to the public of comprehensive, timely, accessible, and reliable statistics. For the fiscal sector, both the SDDS and GDDS provide detailed guidance on data sets and methodologies pertaining to government operations and gross debt.